House of 1000 Manga

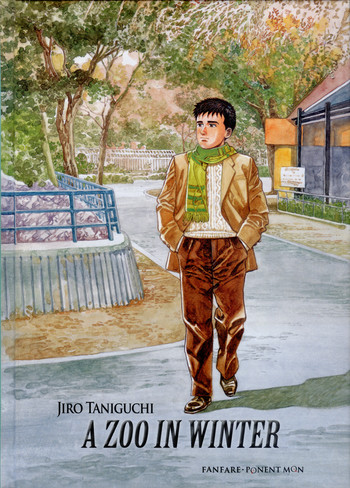

A Zoo In Winter

by Shaenon Garrity,

In my last House column I talked about Yoshihiro Tatsumi's opus A Drifting Life, which follows the manga industry from the postwar era to the year 1960. I wish Tatsumi, who passed away earlier this year, could have drawn a sequel about the second half of his career, during which he became one of the founding fathers of manga for grown-ups. But if you're willing to continue that journey with a different, almost equally adept guide, Jiro Taniguchi's semi-autobiographical A Zoo in Winter picks up where Tatsumi left off, in Tokyo in the 1960s. It's almost eerie, how perfectly this master seinen artist unspools the narrative thread left hanging by the pioneer who invented seinen.

Taniguchi's graphic novel is fiction, but the setting is probably similar to what he experienced in the years of his manga apprenticeship, before his professional debut in 1970. When we meet the protagonist, Hamaguchi, in 1966, he's working in textile design, a considerably more practical career than drawing manga. But the textile industry is clannish, running on gossip and medieval mores, and Hamaguchi gets on the wrong side of one of the ruling families. (Many companies in Japan are old-fashioned zaibatsu, family businesses dating to the feudal eras, and traditional craft industries like textiles boast some of the oldest old-boys’ clubs in the world.)

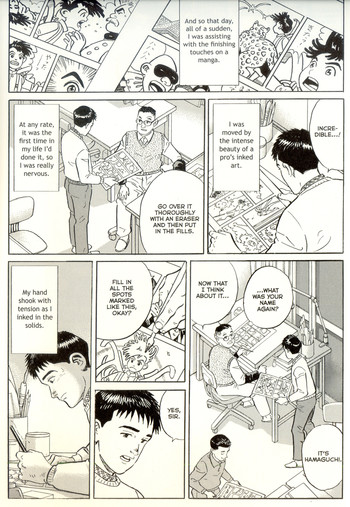

Drifting in Tokyo with no career plans, Hamaguchi runs into an art-school pal who hooks him up with manga work. Literally overnight, he lands a job as a bottom-tier assistant to a hotshot manga artist, one of the top practitioners of a new craft. (In real life, Jiro Taniguchi got his start assisting the late manga-ka Kyota Ishikawa.) Hamaguchi works fast, has no spine, and will sleep at the office if necessary, so the industry embraces him. Workplace politics are vicious here as well: the star artist fobs off work on his assistants to go drinking, the assistants seethe in envy while secretly working on solo manga of their own, and the editor, who pops in at crunch time, makes tantalizing promises she can't keep. But at the same time Hamaguchi learns a lot, gets better at drawing and storytelling, and makes warm and generous friends.

Also, he gets to live in 1960s Tokyo, a fast-moving, bohemian city barely recognizable as the collection of ramshackle buildings inhabited by Yoshihiro Tatsumi's alter ego in a previous decade. It's a place where young artists get drunk and dance with drag queens, hippie folk singers rhapsodize about Legend of Kamui, and there's always a futon open for a runaway who needs a place to crash. Like Tatsumi, Hamaguchi sees his first naked woman during a nude drawing session, but in this more modern era the model is dating one of the cartoonists and hangs out with the gang at a pub afterwards, cheerfully evaluating the sketches of her body. The evocation of the period is the strongest element of A Zoo in Winter; with his crisp, obsessively detailed artwork, Taniguchi plunges the reader into an indelible moment in time. There are revolutions brewing, or seem to be, and the change in the air is intoxicating.

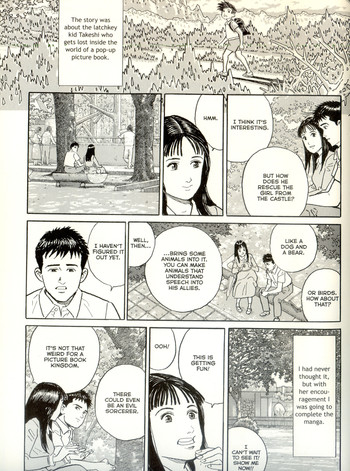

The plot itself is vague, following Hamaguchi loosely through his initiation into the manga industry and his slow development as a manga artist in his own right. At first he's content filling spot blacks for a pro; gradually, he develops the itch to create his own manga. But his dreams of becoming a manga-ka remain idle fantasies until he meets a sickly girl his age who collaborates with him on manga plots. The introduction of a love interest takes the manga in a sentimental direction that some readers may find saccharine, but personally I'm a sucker for characters bonding over comic books. Go, comic books! Save lives and give young people meaning and purpose!

The most emotionally moving sequence of A Zoo in Winter, however, takes place earlier in the story. Hamaguchi's brother, a strait-laced businessman, visits his little brother in Tokyo at the bequest of their worried mother, who hopes Hamaguchi can be talked back into textiles. Hamaguchi is embarrassed to reveal his shabby artist's life: toiling on children's comics in a cheap office by day, sleeping in a cramped apartment by night, and beset at all hours by a rogues’ gallery of hippies, drunks, criminals, and cartoonists. But Hamaguchi's brother, who resembles Don Draper, rolls with every punch. He reveals that he once dreamed of becoming a painter, but gave it up for a more practical career. “It's good, isn't it?” he says. “You're able to do what you like, even if there isn't much money in it.”

In that offhand comment by a tired salaryman, one can hear the frustrated youth rebellion of the 1970s, the swelling and empty bubble economy of the 1980s, the disintegration of the manga industry and every other industry in Japan into chaos and uncertainty. Hamaguchi's brother is one of the engineers of an economic machine that will drive the world, for a while. But the bubble will burst, the engine will sputter, all because of that brief, sweet glimpse of another life. Hamaguchi may not know what the hell he's doing, but he's an artist, and dammit, being an artist is fun.

Even at one modestly-sized volume, A Zoo in Winter meanders. The first chapter feels like a stand-alone story that was expanded into a series at an editor's bequest, which is what it almost certainly is. (Artists aren't so free, really.) The story arc about the sickly girl moves haltingly and ends abruptly, though touchingly. But along the way Taniguchi captures the thrilling uncertainties of an era, a time when even a dead end was an affirmation of life. Maybe Hamaguchi will never make it as a manga-ka. Maybe the girl will succumb to sickness. They're doing what they want, even if there isn't much money in it. And there's more to life than a little bit of money, doncha know?

Like drawing? Like manga? Like tabletop games? If you like any of these things, check out my Kickstarter for Mangaka: The Fast & Furious Game of Drawing Comics!

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |