House of 1000 Manga

Bakuman.

by Jason Thompson,

In honor of my new Kickstarter, Mangaka: The Fast & Furious Game of Drawing Comics, for the next two months I’m going to be writing about meta-manga: manga about manga artists! Please enjoy, and if you like, please check out my new manga-themed tabletop game with art by Ike (Nekomusume Michikusa Nikki) and Eric Muentes! — Jason

“Never create a superficial piece of work. Turn every drop of your blood into ink!”

—The Qualifications of a Man (Otoko no Jôken), Ikki Kajiwara and Noboru Kawasaki

In Understanding Comics Scott McCloud defines “art” as anything that's not directly related to survival and reproduction. It's a definition I like: art is what you do when you're not seeking food, seeking money, or seeking love, whether you're a caveman idly scratching in the dirt with a stick or a modern person drawing a painting or a manga. Of course, if you dissect it a little more, you might wonder if even these motives are free of “survival and reproduction”: do you draw “just because,” or do you draw to become rich and financially secure, i.e. survival? Or do you draw to become famous, and is being famous really about finding a mate, getting the love of others of whom a certain percentage may be smexy fanboys and fangirls, i.e. reproduction? But as an artist you want to believe that there's something more to art than this, some dream, some essence, maybe some magic in the ambition. At some point the pursuit of a craft, or the telling of a story, becomes more than just a way to make a living.

Taka is a 14-year-old with no real goals or dreams. (“I guess I'm just going to live a normal life,” he thinks, unaware that these are fighting words for a manga character.) The one thing that inspires him is love: every day he secretly draws sketches of Miho Azuki, the beautiful girl who sits ahead of him in class. Then one day his classmate, glasses-wearing brainiac Akito Takagi, finds his sketchbook. Taka is annoyed because the art was private, but Akito praises his talent. And he makes a proposal: “Let's make a manga together!”

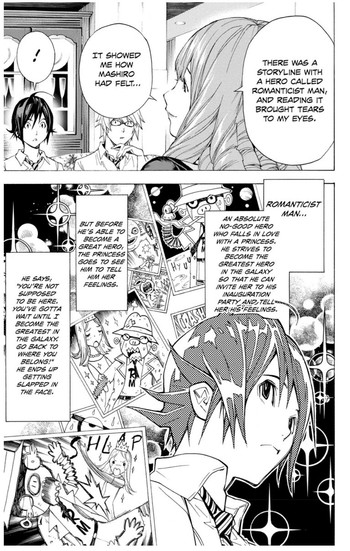

Akito is all gung-ho about this scheme, but Taka is skeptical for very personal reasons: his uncle Nobuhiro was a manga artist, who used to drop by when Taka was a kid, but Nobuhiro never really became a hit creator and he died of overwork when he was just 35. “It's impossible to make it as a manga artist,” says Taka. “The only people who truly do are geniuses born with that kind of talent. The others are nothing more than gamblers!” But Akito knows a secret: Miho Azuki also has a wild dream, the dream of becoming a voice actor! Unafraid of taking chances, Akito drags Taka to Miho's house where they both confess their shared dreams. Emboldened, and realizing for the first time that Miho likes him back, Taka adds: “We were wondering if you'd be interested in doing the voice of our heroine if our manga ever becomes animated…and…if that dream comes true…will you ever marry me?”“Yes,” she answers. “I'll wait forever!”

And just like that, Taka and Miho are engaged to be married at age 14. To a cynical adult, it might sound crazy, but people like love-at-first-sight romances for a reason. But there's an extra catch for our hero and heroine: at Miho's own request, they promise not to proceed in their relationship, or even hang out together, until after they're both successful in their careers. “That way we can both chase our dreams without losing our focus,” Miho tells him. For each of them, the other will be the star they wish upon, the North to which their compass points, supporting one another even though they only communicate by occasional texts. If this sounds like an unusual romance manga, get this: this manga also spans 10 years as Taka and Miho chase their dreams, going from middle school to their mid-twenties. It's always about manga (sadly, Miho's dream stays in the background, more about that later), but it's about love too: the dream-dance of love and ambition, of wanting to find the right person, but not wanting to settle, wanting to be the best.

Bakuman, the second manga teamup of writer Tsugumi Ohba and artist Takeshi Obata (Death Note), is a love letter to the manga industry done in old-school shonen manga style. Like Death Note, it's an extremely text-dense manga, eye-damagingly so; unlike it, it lacks fantasy elements, although Obata's art is actually more cartoony, with lots of exaggerated faces, probably to lighten the mood. (You've got to do something when the action consists mostly of people sitting at their desks drawing, and MAYBE talking on their phones, if you're lucky.) Manga about manga work because the medium isn’t completely transparent—there's many manga fans who dream of making manga, probably more than TV viewers who dream of making TV shows—and also because good writers write what they know, for better or worse, like all those Stephen King novels where authors are the main characters. The dream of becoming a superstar mangaka is a big dream for many people, and a more believable one than becoming a ninja or pirate; not just to Japanese wannabe artists but to many Americans for whom the manga world is an exotic Dreamland Japan of endless opportunity (the land of manga).

In short, if you think becoming a mangaka is the awesomest thing ever, Bakuman isn't here to disabuse you of that notion. This isn't an industry exposé, it's a heroic story of self-improvement, friendship and striving to succeed. (It's much more conventional than Death Note.) But if you like manga, it's fascinating for what it reveals about the manga industry: from coming up to a pen name to coming up with ideas, from nitty-gritty details of drawing to the horror stories of sleep deprivation and peeing blood. This is a manga about the Shonen Jump slogans of yûjo (friendship), doryoku (perseverance) and shori (victory): a self-referential manga that embodies these ideals at the same time that the characters talk about them. Over the course of the series, Taka and Akito draw several different manga, each one a different stage in their growth as artists: from Akito's early high-concept science fiction ideas like “The World is All About Money and Intelligence” and “Future Watch” to stories made at their editor's suggestions, like the gag manga “Vroom, Tanto Daihatsu” or the fantasy adventure “Stopper of Magma” and their final battle manga “Reversi.” A running theme throughout the story is, should manga artists draw what they want to draw, or what they think will sell? Or to rephrase that choice more generously, should they draw what they want, or what the readers want? Different characters have different strong opinions on the topic (“Manga is a basis for self-expression, a personal form of creative art!” “No! Your manga is a product that has to satisfy your readers!”), and one sense the series never entirely answers the question. (“Everyone's different, so everyone's gotta work the way they feel is right.”) But in another sense the series answers on the side of commercialism, for the heroes’ explicit goal is not just to have *A* popular manga, but to have *THE MOST* popular manga. “If you just want to enjoy yourself, you might as well be creating dojinshi. But you're a pro who has a series in Jump. Your priority is to create something that the readers will enjoy!”

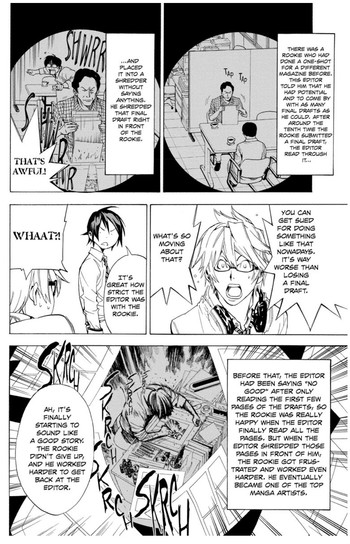

Though it touches on universal questions for artists, this series is also very specifically about the Japanese manga industry, specifically about Shonen Jump. After all (cue Jump self-flattery), Jump where Bakuman ran is the #1 bestselling manga magazine in Japan, so for two guys who want to be #1, there's no other place to work,right? After putting together their best work, our valiant heroes go to Tokyo and make an appointment with the Jump editors, who recognize their talent and pick them up. The Japanese manga industry is still based on close collaboration between editors and artists, and Taka, Akito and all the major characters are paired up with editors who steer their work in a certain direction and try to make their manga as good as can be (i.e. to sell as much as possible). The main editors who work with our heroes are fictional, but real-life Jump editors appear as well, including Hisashi Sasaki (he's on Twitter and often tweets in English about the US Shonen Jump) and the even more venerable and mysterious Kazuhiko Torishima, Akira Toriyama's hardass former editor who had a hand in several hits of the ‘80s and ‘90s. (In one anecdote, Torishima puts an artist's work in the paper shredder right in front of him—is this an urban legend or was it real??) Hattori, the heroes’ first editor, gives them much-needed criticism: Akito's storylines are more like a prose novel than a manga, Taka's art is more like still illustrations than manga, etc. They take the advice to heart, try again and improve. But then Hattori is transferred to work with another artist and the heroes are paired up with a new editor, Miura. But Miura's advice isn't as good as Akito's, and their ratings for their new series start to suffer. As they begin to get the sneaking suspicion that Miura's taste sucks, they have one of their first challenges as creators…

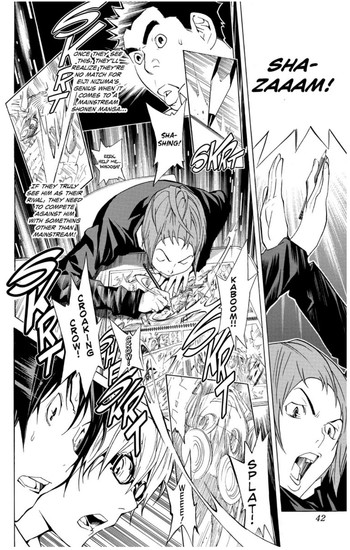

Thus begins our heroes’ adventures, as they take on the challenge of their first manga series while still in high school (!!), risking their grades and their health to draw, draw, draw. If you're reading Bakuman as an aspiring artist, perhaps the best lesson to learn from it is the incredible importance of revisions; over and over the heroes have a not-quite-perfect idea, but with a little polish, a little twist, it becomes so much better…or they discover that the core idea was flawed and then it's literally back to the drawing board. They become friends and rivals with other Shonen Jump artists, chiefly Eiji Nizuma, a kind of childish idiot savant mangaka who has drawn manga since the age of six, wears sweatpants all the time, and is so fast he can draw two simultaneously weekly series (40 pages a week!!). The opposite of Nizuma is Kazuya Hiramaru, a self-taught artist who had never read a manga before he was 26, at which point he suddenly quit his salaryman job and started drawing the bizarre gag manga Otter No. 11. A born cynic, Hiramaru frequently regrets his new career and spends a lot of time moaning and whining and trying to escape his editor (“I took a wrong turn on the road of life to get here…me, a manga artist…ridiculous…”) Then there's Shinta Fukuda, a macho dude, typically seen drawing stories about thugs and motorcycles with an energy drink clutched in his teeth. Fukuda is all about violence and panty shots and all the stuff that shonen manga used to have in the “good old days.” (“We need more unhealthy boys’ manga! We're not trying to create the Bible or a school textbook! Freaking the PTA out is what it's all about!”)

I said they risk the heroes grades and their health; they also risk their relationships. Or do they? The core fantasy at the heart of Bakuman—no more unbelievable than the idea of two people agreeing to it—is Taka and Miho's promise that they will both avoid each other, focusing entirely on their careers, and not consummate their love until they're both successful. Bakuman doesn't use the word “consummate”—this is too shonen a manga to talk about sex—but the motivation is clear, the idea that love is a prize that belongs to the victor. Suppressed desire is the best fuel for working hard, art really is about reproduction after all. Akito makes this a point of pride: he can't be distracted by love, because he'd be a crappy boyfriend anyway, and furthermore his pride demands that he put manga first (“If we're going to get married, I'd rather do it after I succeed in manga. I don't want to end up as a freeloader or something.”) But surprise! Akito does succumb to the allure of love and gets a girlfriend before the end of the series, while Taka and Miho stay pure to their promise, despite occasional moments of weakness. “Maybe true love means accepting everything your partner wants…and helping them achieve it,” Taka thinks at one point. For a 14-year-old Jump reader, Miho and Taka's relationship is a fantasy of pure, almost asexual love. For an older reader, it might be something else entirely, perhaps a fantasy of never having to choose between a relationship and a career.

Although I said this wasn't an industry exposé (and it really isn't; there's nothing here about print manga's declining sales figures), one of the interesting things about Bakuman is having a peephole into the industry, finding out the secrets details about how manga is made. For anyone who's followed the history of manga censorship in America, or Japanese manga scandals like the 2009 Sket Dance helium incident, it's especially interesting to find out the details of what is and isn't permissible in Shonen Jump in Japan. “We can't show humans killing other humans!” a Jump editor criticizes one storyboard in volume 8. In volume 9, another editor suggests changing the word “God”: “‘For a shonen manga like this, it would be better to be vague and say ‘A mysterious and powerful being.’” “Write what you want and I'll worry about the PC police,” a more lenient editor tells his artist. Ryo Shizuka, a hikkikomori mangaka introduced later in the series, has incredible talent but can never get an ongoing Jump series because all his ideas are too misanthropic and depressing.

Akito and Taka, unlike Shizuka, aren't trying to be antisocial, but censorship elements come to the foreground when our heroes create their series Perfect Crime Party, about high schoolers who perform victimless but technically illegal pranks and schemes. “This manga depicts breaking and entering. The main characters trespass on school grounds. We don't want children to imitate that,” one editor complains when the series is pitched. “By that logic, we shouldn't run any manga that shows people punching each other!” another editor argues. Perfect Crime Party gets printed and is a hit, but only up to a point: Akito eventually learns from his editor that it receives a small but steady stream of angry letters from parents, not enough to cancel the series, but enough that it will never be quite “safe” enough to become an anime. Eventually, the criticisms get to Akito, and he starts self-censoring Perfect Crime Party without realizing it, until his editor points it out: “You must be creating something that people will not complain about on an unconscious level.” But the safer, tamer PCP (note that since this is Japan, parents apparently don't know enough drug terminology to complain about the acronym) starts to lose popularity as its core fans get disappointed. Akito is left with a tough choice that all artists face at some point in time: stick with his guns even though some people are pissed off, or compromise and quit because of a vocal minority of complainers?

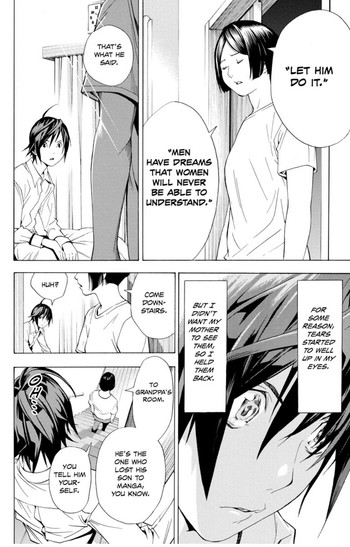

Of course it isn't censorship to say that something sucks, and there's much to complain about in Bakuman too. Readers who disliked the irrationality of the female characters in Death Note (my H1000M partner Shaenon Garrity called Misa in Death Note “the stupidest creature on Earth”) will find more confirmation in Bakuman that Tsugumi Ohba, the author, is one sexist dude. Even by shonen manga standards, Bakuman is sexist: not in a casual “here's some panty shots” way, or a self-aware “look at this crazy sexism, we know it's wrong but we're just jokin’, honest” way, but with the unapologetic stance of a conservative praising old-fashioned attitudes. Of course, you don't have to be a right-winger to enjoy the classic manly manga that Ohba namedrops in Bakuman, like Ashita no Joe, Kyojin no Hoshiand Sakigake!! Otokojuku—the ‘60s-‘70s Japanese idea that manga is a “man's world” like sports and martial arts (really, that everything worthwhile is a “man's world”) is the kind of thing lovingly parodied in the works of Kazuhiko Shimamoto—but in Bakuman there's no parody at all: the main female characters are either bitter, man-hating viragos motivated by grudges against men who rejected them (like Iwase, who becomes a manga artist just to show up Akito), or patient helpmates whose role is to support their men and cook them dinner (like Miyoshi, the girl Akito chooses). The dismissal of women goes back even to the first relationship of child to parent: Akito, Taka and other male characters who show up later have antagonistic relationships with their moms, stereotypical ‘education mamas’ (kyoiku mamas, a bit similar to the modern stereotype of “tiger moms”) who hate manga and continually pressure their sons to be ‘normal’, to study and succeed. It's the fathers and uncles—offscreen, distant, godlike figures in classic manga style—who support their boys, uttering lines like “Men have dreams that women will never be able to understand.” As for Miho, her quest to become a voice actress takes place mostly offscreen, and at one point she turns down a great job in an anime because it's based on a manga by Taka's rival. As Akito says in the first volume, when they're still in school: “Miho naturally knows that a girl should be graceful and polite…and because she's a girl, she should be earnest about things and get average grades. She knows by instinct that a girl won't look cute if she's overly smart.” There's one or two teases that, if you're an extremely generous reader, suggest Ohba might be self-aware about what he's writing, like the line “It's a boy's manga, so we just need to come up with a boy's idealization of a girl,” but a general men's-club attitude emanates throughout. The only female mangaka of any imporance is Ko Aoki, who comes across as uptight, prim and proper (“I just can't stand reading about drugs and whatnot in a boys’ manga magazine!” “Your work is too violent!”), although eventually she is humanized a little and shares manga tips with the heroes; they advise her on how to use panty shots to attract male readers, she tells them to use cute animals to attract girls.

It's a shame that Iwase, the manga ice queen, is such a cliché, because otherwise the villains of Bakuman are some of the most interesting characters in the story. (Perhaps because this isn't a fighting manga and the heroes can't just physically kick their asses…although they do try.) Nakai, introduced as a mopey, sloppy 33-year-old working as an assistant for a mangaka half his age, seems more pathetic than bad at first, but things go downhill for him fast when he gets an unrequited crush on a female mangaka, and his self-pitying “nice guy” act becomes vindictive and sour. Worse than Nakai is Ishizawa, an arrogant talentless guy who claims to be an artist, but can only draw copies of weird cutesy-looking girls with the same generic face. (Isn't there one of these guys in every art class?) Ishizawa eventually debuts as a manga artist in some awful moe magazine, but he's still a creepy otaku perv, and he returns as a villain in the final story arc when he and other 2ch jerks start an online harassment against voice actress Miho for the sin of—gasp!—having a fiancée. (Apparently, even a conservative like Ohba can't stand jerks like the ones who harassed voice actress Aya Hirano.) As a messageboard bully, Ishizawa is a very modern type of villain, and so is Tohru Nanamine, an aspiring manga artist with a dark secret. Nanamine's secret weapon is that he makes his manga by committee, milking free story ideas and art assistance from gullible people he meets online; he's a plagiarist and he's proud of it. But Nanamine's amorphousness eventually backfires, as by trying to please everyone he eventually pleases no one and causes his own downfall (“If you just go around absorbing everything your fans give you, you end up with gibberish! Fan response is all over the internet these days. You can't allow yourselves to be led astray like this!”) His defeat teaches him nothing; later, Nanamine returns even more unrepentant, as the leader of a studio of uncredited artists making manga to fit current trends (“Think of me as something like a movie director!”). Against this wannabe Stan Lee of manga, willing to do anything to make a buck, our heroes (despite their own desire to please readers) represent a purer, more artist-driven attitude…but can they succeed? Or will they be defeated by commercial manga-by-committee?

Bakuman is a flawed but interesting look at the manga industry; it's completely male-dominated, it drags on too long, and the heroes’ singleminded shonen desire for victory starts to seem almost pathological, but it has lots of juicy tidbits for manga lovers. There's much more I could say about it, but perhaps the thing that sticks in my head most is Obata's author note where he reminds the reader that “although this manga is set in the future and spans 10 years, please think of it as taking place in the present.” The truth is that the manga industry is changing so quickly that in 10 years Shonen Jump might be completely different (might even, perhaps, be an online-only magazine), and the editorial and production system might be totally different. For that reason, the parts of Bakuman that talk about general comic-making and artistic philosophy are much more interesting and relevant than the otaku parts that talk about the minutiae of Shonen Jump and Akamaru Jump and how readers’ polls are calculated or whatever. Because the future of manga is uncertain: will it belong to the Tohru Nanamines and Ishikawas? To the Takas and Akitos? Or perhaps to the Ko Aokis, or to a type of artist Ohba can't even imagine? To non-Japanese readers, the world of Bakuman may seem exotic, but perhaps it's just as exotic to Japanese readers, a snapshot of a manga world that's changing fast. Tsugumi Ohba grew up thinking the manga of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s were the greatest things ever. What will manga look like to a new generation for whom the ‘00s and ‘10s are the glory days?discuss this in the forum (21 posts) |