House of 1000 Manga

Sparkler Monthly

by Jason Thompson,

“What kind of people go to these anime conventions? Is it mostly Asians?” one of my elderly relatives asked me once. I took a deep breath and gave her a lecture: anime and manga wasn't something ‘just’ for Asian-Americans, fans of all ethnicities enjoyed Japanese pop culture, and so on. And it's true. The Japanese economic boom from the 1960s to the 1980s wasn't just about selling consumer electronics and cars; it was about selling cultural exports, arts and entertainment and escapism. Just as the US sells a fantasy image of itself abroad, through American TV, movies and superheroes, Japan sells itself too; in America anime fandom cuts across race and class, and globally it extends into the Middle East, Latin America and other places where Captain Tsubasa, Dragon Ball and Naruto resonate much more strongly than locally produced offerings. Japanese pop culture is global pop culture: its capitalistic success is a rare (but nowadays, increasingly less rare) example of cultural power radiating not West—>East, but East—>West, East—>South, East—>East, everywhere that licenses or scanlations take it, a global marketplace of fantasies and desires.

But just how “Japanese” is manga? Is it more or less Japanese, in some essential way, than samurai, ninja, Christmas cake and Shinto? In response to a question of whether white people cosplaying Asian characters from anime and manga was offensive, a friend on Twitter once asked “I thought most anime characters weren't Asian anyway?” And it's true that many of the most internationally popular anime and manga aren't specifically set in Japan: in manga and anime, as perhaps in all media, there's a wider audience for fantasies set in vague composite places (Gotham City is not New York) than more realistic works that require deep knowledge of when, where and why they were made. There's a limited audience overseas for the regional Osaka references of Yuji Aoki's Naniwa Kinyudo, the politics and pop culture minutiae of Koji Kumeta, the manga industry in-jokes of Kazuhiko Shimamoto, or the fetishism of Akihabara consumer culture in Genshiken and other otaku manga. But even shows that aren't specifically set in Japan often bear the mark of being created by Japanese artists for a Japanese audience, such as the casual mention in Attack on Titan that Asians are the rarest and thus most precious race among all the peoples within the Wall, or the stereotypical nosebleeds in comedy manga, or Alphonse in Fullmetal Alchemist fretting that his brother Edward will get a cold if he sleeps with his tummy showing. A friend from Jordan grew up watching Arabic-dubbed anime, with the characters given Arabic names, but found herself wondering at an early age in what part of Jordan people ate rice with chopsticks. Such cultural differences invariably register as ‘weird’ to foreign audiences, but whitewashing them—or making them off limits for discussion—is surely a worse idea than acknowledging them. To be interested in anime and manga is to be interested in Japan, if only to understand the perspective you're watching, though such understanding may be distorted and shallow. For a foreign fan of anime and manga, appreciation of craft and exoticism of Japan are always mixed.

Few fans are entirely content to be in a position of just passively watching and reading and not making or doing, and imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so of course foreign fans absorb manga influence into their own art. Manga-influenced comics have been published in America since the mid-‘80s (or the late ‘70s if you count Elfquest and The Love Rangers), buoyed by a broader interest in Japanese pop culture and, later, by the first licensed English anime releases on VHS. Manga-influenced artists faced prejudice and mockery, at times mixed with racism, from other artists who despised manga and idolized a more nationalistic, “native” style—typically Silver Age superhero comics style in the US, other comic traditions in other countries. “Editors wouldn't piss on you if you were on fire if you were working in the manga style,” said Adam Warren about the ‘80s. For their part, in typical otaku fashion, each new generation of manga-influenced artists prized authenticity, and thought themselves more knowledgeable about Japan, their comics more truly “manga-like,” than the artists that came before. Some manga-influenced artists were as broadly ignorant about and dismissive of Western comics as their fellow nationals were about manga. As a mark of pride, some even identified their work as “manga” and themselves as “mangaka,” a semantic distinction considering that “manga” is just the Japanese word for “comics” and Superman comics might be called “manga” in Japan…but perhaps understandable considering that every new movement seeks a term to rally around to separate themselves from outsiders and from those not-doing-it-right weeaboos who came before. On the rare occasions when major US comics publishers did ‘pay homage to’ manga, like the Marvel Mangaverse, the results were often met with disinterest by manga readers, who considered them superficial, cheesy and a weak attempt to glom onto the growing manga trend (though Takeshi Miyazawa's shojo-ish Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane found an audience).

I've always enjoyed manga-influenced comics—I wrote one, after all—and the great boom of manga-ish comics in the USA, in the mid-2000s, was an exciting time. With the great post-Pokémon flood of translated manga and anime, it was inevitable that manga-influenced Western artists would arise, but what wasn't inevitable was that companies like Tokyopop would actively seek out artists to create what they called “global manga” or Original English-Language manga, “OEL.” From a US publisher's perspective, creating new properties is a no-brainer, since original properties can be merchandised and monetized by the US publisher, unlike Japanese properties where most licensing money goes back to the Japanese publisher and the US side only gets a tiny piece of the pie. (This is also the reason why Cartoon Network now focuses on original content rather than Toonami and reruns of classic Western cartoons. Anime doesn't pay enough.) To appeal to the reader who responded to the words “Japan” or “manga” more than “comics” or “graphic novels,” Tokyopop described their new books as “manga,” and Seven Seas even required their artists to draw from right to left in an attempt to emulate Japanese comics on the shelves. Some good artists debuted around this time: Joanna Estep, Becky Cloonan, Brandon Graham, Lindsay Cibos, Madeleine Rosca, Sophie Campbell…Maximo Lorenzo and Corey Lewis with their outrageous shonen-manga-influenced artwork…Svetlana Chmakova with her wonderful slice-of-life Dramacon…Felipe Smith with his gonzo satire MBQ…and many others. Bryan Lee O'Malley's Scott Pilgrim, James Stokoe's Won Ton Soup, Jen Wang and Kazu Kibuishi's Flight anthologies weren't advertised as “manga,” but could just as easily have claimed the title. It was a rare time of opportunity when inexperienced, manga-influenced artists could get ADVANCES (!!!) and even ROYALTIES (!!!) for drawing ORIGINAL CONTENT (not licensed properties based on games, movies and TV shows!!). The contracts weren't always great, and some of the books were pretty awful, but it was the crest of a wave when it briefly seemed like a new, international-aimed art style and new stories might sweep over the dusty 80-year-old superhero franchises.

It didn't happen, of course; the manga boom crashed, and OEL manga sales tanked especially badly (perhaps because they were “not Japanese enough” for Japan-obsessed manga readers). Some artists switched to less manga-esque styles, as ex-Tokyopop editor (now DC Comics editor) Tim Beedle predicted would happen. Others moved into teaching, video games and other art jobs. Those non-Japanese artists who still draw “manga” (i.e., manga-influenced comics) do so out of deep love for manga and not because manga is a trendy marketing category. Whether their manga influence is mostly stylistic and visual, or born of the storytelling tropes of Japanese comics, if they see themselves as “manga,” well, the superhero fan who asks them “Are you still drawing that manga stuff?” sees them that way too.

One manga-influenced site that stands out is the online magazine Sparkler, running since 2013. Edited by five manga fans of different backgrounds (translators, fans, ex-Tokyopop editors), Sparkler focuses on female-friendly content with influence from shojo manga, which pioneered “comics for girls” in the US back when American publishers had zero interest in female readers. It's a freemium site, so some material is free while some costs money: for $5 a month you can read almost everything on the site, or for an additional $6 you can buy ebooks of Laurianne Uy's Polterguys and other titles. The monthly subscription costs a little more per page than you get from Viz's Shonen Jump or Crunchyroll's manga streaming service, but with Sparkler you're not buying something from a huge corporation; you're supporting a small group of independent artists, much like with a Kickstarter or Patreon. At the time I write this review, the Sparkler pay system was in the middle of an upgrade and revision, so these exact prices may change by the time you go to the site. The main thing is the content: a new PDF “magazine” every month, plus podcasts, prose stories (in an illustrated “light novel” style), and tons of comics.

The prose and audio sections of the site have many interesting stories, including Tokyo Demons, a story about a girl who can transform into a swarm of insects, and Dusk in Kalevia with its mixture of European military uniforms, angels and bishonen. But this is a column about comics, so I'll focus on the comics (or the manga…I'm just going to switch back and forth using both, does anyone really care? -_- ). Sparkler has a handful of short manga stories, some reminiscent of the Boy's Love or yuri genres. Denise Schroeder's Before You Go is the tale of two girls who meet on a rainy train platform: Sadie, a store clerk who dreams of being a singer, and Robin, slightly older and outwardly more mature, who gives Sadie a towel to dry herself off and asks her “You're cute. What's your name?” The series description gives away that it's a girl x girl romance, and once that's established there's not many surprises, but the buildup is pleasant. Shut In Shut Out by Lianne Sentar and dee Juusan is more original, both in terms of Sentar's scenario and Juusan's handsome, highly rendered art: the tale of Rashid and his childhood friend Bo, a shut-in who spends all his life in his apartment wrapped up in a blanket playing online games. “I guess I figured he'd grow out of it,” Rashid tells another character. “But he still won't even try to go out. Ever. And he wants me to live in his little bubble with him…” Were this a Boy's Love title, it'd be easy to imagine it ending with the characters spiraling down into codependence, but instead it's more of a story of friendship, and refreshingly, the arc follows Rashid's attempts to bring Bo into the outside world (“You're the most important person in my life. But you're not my ENTIRE life!”). I'd love to read more about these two characters.

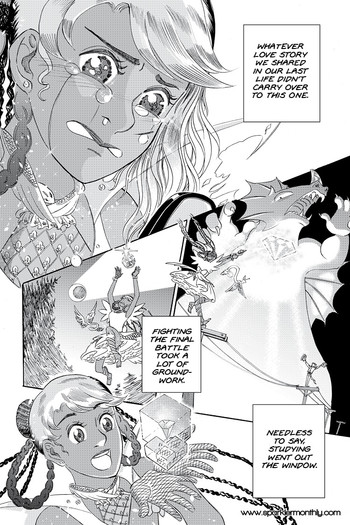

One of the longer stories, KaiJu's Mahou Josei Chimaka, is a parody of Magical Girl manga. The opening scene sets the tone: Chimaka, basically a Sailor Scout, is fighting an evil cloud of darkness with the help of her winged snake friend, Snakey. “Shimmer Shimmer Diamond Reflection!!” she calls out, and raises her wand for the final blast, and then we cut to 15 years later, with a coffee-swigging grownup Chimaka looking out at the giant blast crater left over from that battle and saying “Well, fuck.” Turns out that there was no happy ending: Chimaka failed to save the city, she lost the prince who has her reincarnated love from the past life, she lost Snakey, and now she's in her thirties working a 9-to-5 corporate job as a ’mad scientist’ ( “By ‘mad’, I mean ‘angry at my life’”). When the threat from the past reappears in the form of a massive hole in the ozone layer, the government tries to get Chimaka to step back into her secret heroic identity of Shimmer Shimmer Sky Patcher, but it's not so easy. Her powers don't work anymore. She tries to activate her magic jewelled hairbrush and throws it in the air, but it just falls back down and lands on her head (“Ow, fucker!”). Not knowing what else to do, Chimaka confides in her drinking buddy Pippa. “Pip…I'm a magical girl.” “Yeah? I mean, we're all a little magical, right?”

This kind of thing has been done before—if you've been reading maho shojo, sentai or superhero stories all your life and now you're 30, it's natural to imagine your heroes growing up and perhaps having shitty jobs and swearing a lot—but it's rarely been done this well. KaiJu's shojo-esque art is smooth and beautiful, with a lot of lovely illustrations of plants and nature in keeping with the environmental theme. Like several other Sparkler titles, it's nice to see that the lead isn't a skinny white or East Asian woman, but curvy and brown-skinned; the diverse attention to both race and bodytype makes me want to print out Mahou Josei Chimaka on paper just so I can roll it up and beat the creators of Ugly Duckling Love Revolution with it. And the story manages to be hilariously funny while also keeping a certain mystery and seriousness (and not in a clichéd “OMG this is so dark & depressing, look at all this GORE, guyz, this is so serious” way). I was even more impressed by KaiJu when I read their other Sparkler story, The Ring of Saturn, a historical short story about a European piano student trying to learn to play Gustav Holsts's “Saturn, Bringer of Old Age” while World War I rages around her. A more different story from Mahou Josei Chimaka couldn't be imagined, yet Saturn is even more masterful, a story of great subtlety with powerful expressions of music in visual form.

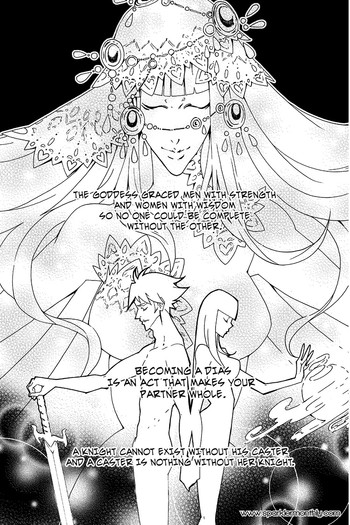

Christy Lijewski was a winner of the Tokyopop “Rising Stars of Manga Contest” and afterwards drew the three-volume Tokyopop series RE:Play, about vampires and a rock band. Dire Hearts is set in a vaguely European fantasy world where women can use magic and men cannot; when men and women bond as one another's Dias, like a wedding ceremony, they vow to support one another with feminine spells and masculine strength. Rose Chevalley is an exception: she can't use magic. Rose's teachers at the academy don't think much of her future prospects (“A woman who can't cast is severely limited in life!” You must hope that a kind man will see past your disability!”), and as a result Rose is the school ‘bad girl,’ a rebel who sleeps through class and doesn't give a damn about anything. But there's something nagging at her: maybe it's the strange scars on her arm, or the fact that she has total amnesia of everything before three years ago. Are her teachers keeping something secret from her, and is there a mysterious conspiracy centered on her own past…? Like Rose, I want to know more, but at the time of this review there's less than 50 pages of Dire Hearts so a lot is still unrevealed. It's an interesting setup that reminds me of Revolutionary Girl Utena and other occult/gender-themed anime, but Lijewski's super angular artwork is slightly distracting; there's not a lot of depth in the compositions, and all the characters look stretched out and bony with huge hands and pointy hair.

One of the most visually manga-like titles is Orange Junk by Heldrad. If it wasn't mentioned that Heldrad was from Mexico I could easily think the artist was Japanese, so perfectly does the story (and art, for that matter) replicate a 1990s shojo manga. Louise Barton is a sheltered rich girl whose family has fallen on hard times, forcing her to go to (gasp!) a public school while her mom works as a door-to-door saleswoman and her dad mopes gloomily. At her new school, Louise is horrified to behold such low-class sights as students with mohawks (gasp!); her math teacher, Jack, is an ex-thug with dark glasses, a leather jacket and four-day stubble; and her violent classmate Bruce mocks her with “This isn't some private school where you can just pay out of your grades! This is why I hate rich bastards!” The only thing that makes her new life bearable is Andrew Gray, her super-handsome, super-sweet classmate, but Andrew's actually a spacey ditz who sings along to anime songs and gets distracted looking at the clouds (“The clouds are fluffy today!”). Surprise Number 2: brutish Bruce is secretly a super-genius, and he ends up becoming Louise's math tutor! With the two men in the love triangle being a sexless, Pollyanna-ish space cadet and a grouchy jerk, it's easy to guess who our heroine will end up with; later the storyline turns to Bruce's impoverished background and Louise visits his crumbling house in the slums where he works to support his loving mother and siblings. (“What a warm home…” she thinks.) Unfortunately, although the Sparkler websites advertises Orange Junk as a parody of old shojo manga, the weak heroine, tsundere love interest and unsubtle class elements feel more like a recycling of tropes than a parody of them. Although the setting isn't explicitly named, one of the most interesting things about itis that it seems to be set in America: a slightly unconvicing cartoon America where people eat hamburgers and have names like Jack and Andrew and Bruce, not unlike America in the manga of Minako Narita, a reminder that exoticism flows both ways.

There's nothing better than the thrill of discovering an artist who's totally unique, and that's the thrill of reading Alexis Cooke, whose artwork reminds me of Natsume Ono and Tove Jansson and Patalliro but it's really like nothing I've ever seen. Her tapestry-like compositions feel like 1970s shojo manga, with delightfully original use of flowers, emoticons and sound effects drawn with fine thin lines, but her character designs are from another world entirely, handsome men and women with huge noses and pretty, long-lashed eyes. Dinner Ditz, a short story of a few chapters, is the tale of Peregrine, a divorced gay man trying to learn to cook so he can be a better father to his daughter. Help comes in the form of Otho, his cook neighbor, whom Peregrine accidentally runs into in the hallway after one particularly disastrous cooking experiment. Did I mention that Otho is quite fetching? This charming character piece surprises in all kinds of ways, from Peregrine's friendly relationship with his ex-wife Dottie (“You're the best ex-wife any gay could ask for, Dottie!” “Awww! You're the best ex-husband any small-town girl could want!”) to his relationship with his daughter, a character much more complex than the typical moe daughter pixie seen in manga. Most of all, I never thought I'd read a comic that made the “they suck at cooking” cliché actually funny. Alexis’ other ongoing Sparkler story, For Peace, is also a romance. Following two lesbian truckers, youthful Lillian and more experienced convoy-leader BeBe, it follows them through their struggles as they try to balance love with the demands of trucking and life on the road. As Lillie's mom teases her “You only get this excited over fast cars and girls!”

For romance in the word's older sense of “adventure” (a la Alexandre Dumas), there's Windrose by Studio Kosen, a pair of artists from Spain. In 17th century Spain, Daniela, a teenage noblewoman, runs away from home, following instructions in a letter from her absent father who also leaves her a mysterious astrolabe. She soon discovers that the astrolabe is the clue to a priceless treasure: “the voice of storms,” a magic artifact that controls the seas, and whatever nation controls the seas controls the world! Her father was a secret agent trying to help Charles III, the true king of Spain, regain his throne from the French-installed puppet monarch. But danger lurks along the way to the artifact; pirate attacks, evil French agents, and two roguish travelers, the beautiful swordswoman Angeline and her equally handsome brother Leon. After Angeline robs Daniela and Daniela hunts her down, the strange trio become reluctant allies to find the “voice of storms”…but can the two thieves really be trusted? It's a promising historical story full of fancy costumes, fancy balls, swordfights and secret passages, drawn in a realistic style that might appeal to both manga- and non-manga-readers. (The realism ends at those perfect faces and jewel-like eyes.)

One minor thing about Sparkler is that, with the exception of Tokyo Demons, none of the stories are set in Japan, at least not obviously. I'm often skeptical of Western comics set in Japan, but I don't think it's innately wrong (Felipe Smith did it well); at worst these stories can be clichéd or invested with a false sense of authority, but at times an outsider perspective can be interesting, even if (perhaps especially if) it tells us as much about the creator's fantasies as about reality. The narratives of tourists and travelers have value, like French artist Frédéric Boulet's many pseudo-autobiographical comics about his life in Japan. Boulet, notably, had zero interest in ninja, samurai, galge and all the mystical or technological stuff usually associated with Japan in Western minds: what inspired him about manga was the realistic observation of setting and daily life found in seinen and josei manga (and anime like the works of Isao Takahata), something rare in the fantasy-oriented stories of his native French comics. Writing an artistic manifesto for what he called the “Nouvelle Manga” movement, he invited French and Japanese artists to work together, to make stories that used the best techniques of both countries to create comics not set in generic fantasy worlds, but in a specific time and place.

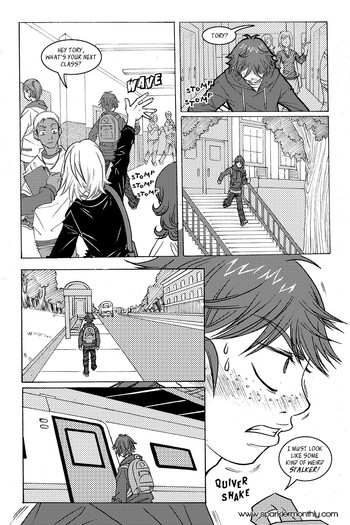

I don't know if she's a fan of such manga, but Jen Lee Quick's Off*Beat is a great example of these techniques. Set in the New York suburbs, this slow-paced story draws us in with its incredible realism, its backgrounds and environments, the kind of extreme attention to detail that many manga artists frankly cheat at by hiring assistants to draw. It's the story of Tory, a high school student who becomes obsessed with his new neighbor Colin, who he sees one night moving into the duplex down the street. “There's something here that I can't explain…something different about him…” he thinks. We slowly discover that Tory is a bored genius who gets straight A+s and who keeps meticulous notebooks about everything, and soon he's spending all that time and energy studying Colin, enrolling in a special private school just to go to the same school as him, sneaking into the office to read Colin's school records, and setting up a study group just so he can spend more time with Colin outside of school. “Your little detective case happens to be an actual person…you're a scary kid,” teases Paul, Tory's scruffy slacker neighbor who comes downstairs to play video games with Tory and eat leftovers cooked by Tory's mom. As for Colin himself, he's brooding and standoffish, but he's really a normal kid…or is he? What exactly is the “Gaia Project”, run by Colin's legal guardian, Dr. Garretts? Is Tory insane, or is Colin the weird one after all?

Off*Beat is one or both of two things: (1) one of the most subtle, realistic Boy's Love stories I've ever read (2) a psychological mystery about a brilliant, neurotic teenager and his self-destructive obsession. After a slightly abrupt start the pacing is wonderful, a long slow burn that must have required as much patience from the artist as it does from the main character. It's a good example of the truth that the specific beats the general; only an East Coaster who attended an American high school could tell this story so well. Off*Beat is complete in three 200-page volumes, but Jen Lee Quick also has two other stories on Sparkler; although fantasies, unlike Off*Beat, they share the same great art and great sense of place. Witch’s Quarry is a maybe-romance set in a world of magic and monsters, in which Veolynn, Lady Knight of Chrisbury, rides out to attend her brother's arranged marriage to a foreign sorceress and finds herself caught up in (sexy) intrigues. Gatesmith is perhaps the Sparkler manga I'm most excited to read more of: a Wild West tale which opens with a brutal scene of violence then subsides into a slow, creepy buildup as supernatural events begin to plague the small Western town of Edgeward. Doc Malik, a black cowboy, and Ashkii, a Native American cowboy who tells tales of witches and skinwalkers, are soon joined by Miss Morgan, a mysterious drifter; while meanwhile Lucrezia Cruz, a lady scientist from the East, comes into town to meet her mentor, Professor Emile, who may have been experimenting with Things Humans We Not Meant To Know. (No, it's not a Cthulhu story. Probably.) Mutilated animal corpses…strange glowing lights in the desert dusk…tentacles that turn into trees (and back again?)…it's a cool story, moving with the slow confident pace of the best manga, towards unknown territory.

Neither fully “manga” nor fully “Western” (whatever either of those terms means), manga-influenced comics are often fascinating precisely because they don't fit into any one market or mindset. Mainstream manga, although technically creator-owned, is often so editorially controlled that it's totally predictable, and even the mind tricks of Grant Morrison can't make a DC or Marvel comic exciting for me anymore since I know it'll all be retconned the moment the next movie comes out. On the other hand, indy artists from Canada, Mexico, the USA and Spain drawing comics in a Japanese-influenced style might be the best possible outcome of globalization. (The worst? Dragonball Evolution.) Sparkler is just one of the best of thousands of small groups and artists remixing culture in their art,sometimes skillfully and respectfully, sometimes crudely, but always bravely and according to their own personal interpretations of that art and culture. Manga is by definition Japanese, like manhua is Chinese and manwha is Korean, but it's also international. This is its strength. As I told my old relative, it's for everybody.

discuss this in the forum (21 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history