House of 1000 Manga

Helter Skelter and Pink

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

Helter Skelter and Pink

A word before we begin: a laugh and a scream are very similar.

This line, from the opening of Kyoko Okazaki's Helter Skelter, could be printed on the first page of any of her work. As many artists have tried to do and precious few have done well, she walks the tightrope between comedy and tragedy, laughter and terror, ordinary life and nightmare. Although it's hard to think of two manga artists who are more different stylistically, Okazaki embodies horror giant Kazuo Umezu's adage, “If you're doing the chasing, it's a gag manga. If you're being chased, it's horror.”

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Okazaki was a manga rock star. She was one of the pioneers of “gal manga,” a bold, raunchy, explicit new style of manga for young women who liked to work hard and party harder. It was the ’80s, after all; Japan had changed from struggling postwar casualty to high-tech economic superpower with head-snapping speed, producing a glittering, baffling new culture. Gal manga satirized the bubble economy and its bubble-headed young beneficiaries, but with enough glamour and glitter, fashion and fame—and, above all, lots and lots of sex—to raise the question of whether the artists were mocking the excess of the age or celebrating it.

And for young, middle-class women of the time, there was a lot to celebrate. They had unprecedented freedom and opportunities. They could make and spend their own money, have sex on their own terms (and unlike the U.S., Japan didn't have an HIV epidemic to dampen the party mood), and settle down when and if they felt like it. So maybe the gals sometimes earned their reputation as shallow, image-obsessed party girls. Maybe, once in a while, some innocent bystander got gobbled up by the crocodile of life. It was still a thrilling time to be young in Tokyo.

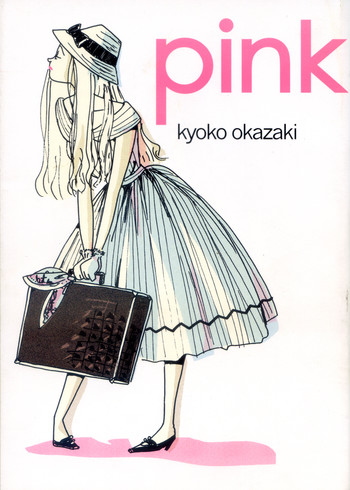

Okazaki's first major manga, Pink, one of two works available in English, captures the zeitgeist as a bubblegum fantasy mashed between sharp, sharp teeth. Antiheroine Yumi is an office lady by day, call girl by night, and finds both jobs about equally boring and degrading. But she needs money to live the celebrity lifestyle of her dreams—and to feed her pet crocodile, Croc, which menaces the men she brings home to her apartment while Yumi giggles. Traipsing through urban life without a complex thought in her head, Yumi is too self-centered for friends, but she dotes on her smart, cynical little stepsister Keiko. The two gals bond over their mutual loathing of Keiko's mother, an aging, vindictive trophy wife who's basically Yumi in twenty years.

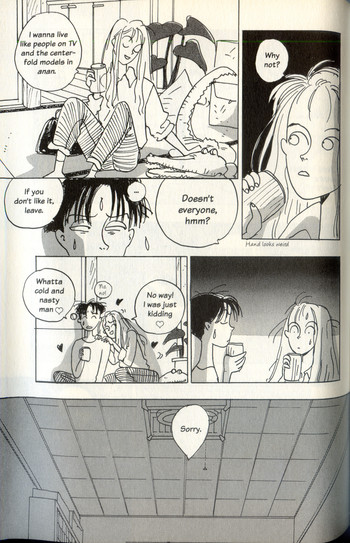

When a hapless, corruptible young writer named Haru gets ensnared by this family of cold-blooded man-eaters, the dynamic is perfected. Maybe life with Yuki (and the crocodile) will inspire Haru to stop futzing around and write his novel. Or maybe she'll make him give up and admit that beneath his lofty thoughts he's as shallow and mercenary as the rest of them, that everyone in this world is living in that old joke with the punchline, “We've already established what you are, madam. Now we're just haggling over the price.” Okazaki called it a story of “love and capitalism.”

Yuki and her world are scribbled out in the loose, casual sketches of an artist who knows she's too good to need to show off. The characters have dots and parentheses for eyes, squiggly lines for hair. Everything about the manga feels casual—the poses, the pacing, the nudity—but there's a neurotic thrum to Okazaki's line, an undercurrent of danger.

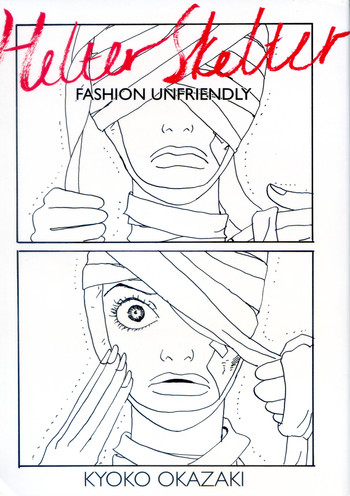

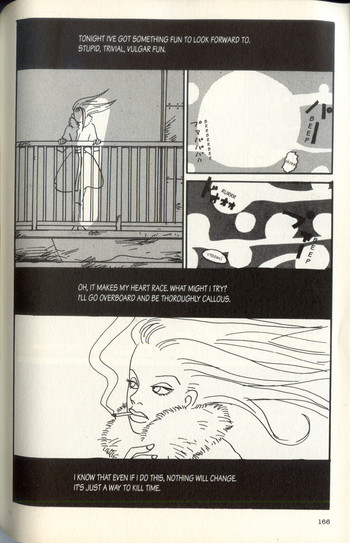

Pink, published in 1989, marked Okazaki as a sardonic critic of modern life and disposable pop culture. Helter Skelter, her most recent work, has a similar but even darker and more cynical worldview. The story builds off a familiar science-fiction premise: a miracle surgery that bestows youth and beauty at a too-high price. In this case the recipient is sexy pop-culture princess Liliko, a model/actress whose body is as fake as her cutely polished public persona. “Everything except her ears and a portion of her genitalia are fake,” claims one gossip. But the extreme beauty treatments don't last, and no matter how many upgrades Liliko's handler, “Mama,” forces her through, her lucrative body keeps decaying around her. Increasingly unhinged, Liliko takes out her frustrations by smoking, drinking, throwing temper tantrums, and plotting revenge against enemies real and imagined.

Like Yumi in Pink, Liliko is flighty, self-centered, vicious, and vacuously preoccupied with appearance and celebrity culture. But Liliko is a darker and nastier character. Where Yumi fantasizes whimsically about feeding people to Croc, Liliko takes out brutal hits on her rivals. Where Yumi playfully torments Haru, Liliko physically, emotionally, and sexually abuses her long-suffering PA. Yumi's moonlighting in sex work has nothing on the way Liliko uses her body as a blunt instrument to get at what she wants. And Liliko is literally falling apart.

Part science fiction, part body horror, part satire of the beauty industry and the cult of celebrity, Helter Skelter is a grotesque manga about prettiness. In both Helter Skelter and Pink, Okazaki loves peeling back the skin of femininity to poke at the sex and violence writhing underneath. She sprinkles her manga with her own leering sketches of Pink Think cultural detritus: Barbie dolls, Disney princesses, Marilyn Monroe, bondage porn. The great josei/seinen manga-ka Moyoco Anno learned her trade as Okazaki's assistant, and it's easy to see the Okazaki influence in Anno titles like Happy Mania, Flowers and Bees, and Sakuran. But not even Anno's snarkiest work plumbs the depths of the shallow human soul like Okazaki's gal manga.

Pink and Helter Skelter are just two of the many manga Okazaki churned out in her brief, bright career. In 1996, as Helter Skelter neared completion, she was hit by a drunk driver while out on a walk with her husband. Left paraplegic, she has yet to recover from her injuries. Moyoco Anno finished Helter Skelter from her sketches and has since pushed to keep her mentor's work in print.

Okazaki continues to be a major influence on josei manga, alternative manga, and the French/Japanese nouvelle manga movement, but no one who followed her has ever been so brilliantly cruel or gloriously nasty. There's heart to her work, but never sentimentality. As she wrote in the afterword to Pink, tongue no doubt firmly in cheek, “All work is prostitution. And all work is love as well. Love. Yup, love.”

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |