House of 1000 Manga

Children of the Sea

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

Usually, with these columns, I start with the story, because I'm human and humans love stories. Then I talk about themes and ideas and styles, and finally I get around to trying to describe the art. But with Children of the Sea I have to start with the art, as fascinating as the story is, because this is one of the most beautiful manga in the world.

Daisuke Igarashi has the funky, sketchy indie look common to many of the manga from alt-manga magazine Ikki, which also gave us Saturn Apartments, House of Five Leaves, Sexy Voice and Robo, and, more recently, Taiyo Matsumoto's Sunny. But he also draws with detail and precision, lavishing attention on elaborate panoramas of sea life and the natural world He can draw emotion as well, and those quiet supernatural moments when something appears just enough askew to be terrifying. Above all, he captures the feeling of the sea: of vertiginous depths and infinite grey skies, of shadows in the murky distance, of seagulls and sand fleas, of the womb.

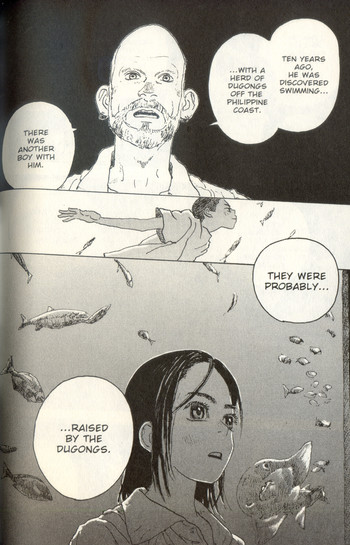

Ruka lives in a small seaside town, where she plays sports a little too aggressively, rides her bike along the forest trails, and has trouble making friends. Her parents work at the local aquarium; her mother, we learn much later, was raised as an ama, a traditional diving fisherwoman. Ruka has had some unexplained experiences growing up, but so, it seems, does anyone who spends much time around the ocean. Then something truly strange comes to her town: a pair of boys about her age, UMI and Sora, who live in the water like sea creatures. The scientists at the aquarium think they were abandoned as infants and raised by dugongs. As Ruka gets close to the friendly but unreadable UMI and the antisocial Sora, she begins to suspect the truth may be more complex and even harder to believe...

For the first volume, it feels like we know roughly where the story is going. Ruka balances her ordinary small-town life with investigations into the mysteries of the sea, in the process developing feelings for both mysterious boys. But just when we think we're on board for a slightly magical coming-of-age story, things kick into high gear. Bizarre oceanic phenomena break out all over the world, from sea creatures turning up in the wrong latitudes to corpses washing ashore to rains of fish. Ruka meets other people who are studying UMI and Sora, all of whom seem to have different theories about what they are and what their existence means. She comes to understand that whatever is happening in the ocean, it's big—much bigger than the human race. Eventually the three young people set out to sea, not entirely sure what they're looking for. As Ruka's involvement with the boys deepens, she drifts away from humanity herself, toward alien depths.

We never do find out exactly what's going on in Children of the Sea. Things got clearer for me on the second reading, and I'm pretty sure I could tell you what everyone's deal is, but the manga isn't particularly interested in explanations. Like Inio Asano's Nijigahara Holograph, which it sporadically reminds me of, it's more interested in presenting questions and exploring mysteries, and in the end it's as unplumbable as the sea itself. The characters talk about how the ocean takes up most of the Earth's surface, and how little of it has been explored by humans. They talk about the dark matter in space, and how almost all the universe is made of substances that have never been observed. Yes, this is the kind of manga where characters talk about astrophysics. And genetics. And mermaids and selkies and Indonesian shadow-puppet plays. And maybe it all ties together, or maybe it falls apart between the cold tweezers of logic. Maybe it's better to just let it be beautiful.

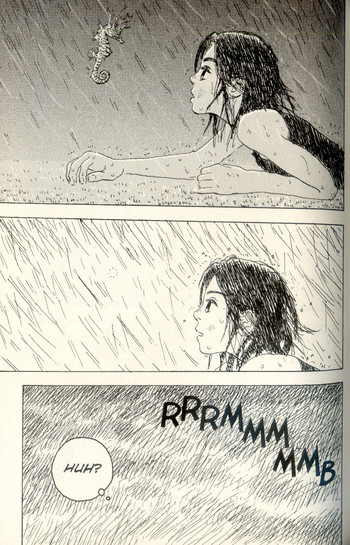

And, again, this is a beautiful manga. The characters have inquisitive eyes and knobbly knees, and Igarashi loves to draw their individual body language. Unlike a lot of manga artists, he draws a wide range of body types: skinny kids, tattooed old men, women with buckteeth and wild hair. Then there are the sea creatures. I'm inclined to suspect the “oceanic life shows up in the wrong places” plot point was introduced primarily so Igarashi wouldn't have to restrict himself to drawing only species native To the Sea around Japan, but could bust out with killer whales and lionfish and giant sea turtles and whatever else struck his fancy. He's one of those artists, like Hayao Miyazaki or Winsor McCay, whose pleasure in drawing radiates from the page. The final chapters of Children of the Sea dissolve into a collage of teeming underwater vistas. Before that, the manga overflows with visuals that stick in the mind's eye. A seahorse hovering in a rainstorm. A whale marked with the image of a goddess, like a massive tattoo. A black manta that becomes a dark, staring face. The movements of a starfish, drawn with observant care. Fish dissolving into light.

Igarashi is not a prolific manga-ka, and to my knowledge Children of the Sea, at five volumes, is his longest series. Before that, he was best known for the critically-acclaimed fantasy Witches, which is similarly preoccupied with folklore, the supernatural, and the relationship between humans and nature. Viz published Children of the Sea as part of its SigIkki line, about which I've written before. It was almost certainly the best of many strong titles. Since then, it seems to have been lost in the manga shuffle; I don't see much discussion of it on the English-language Internet. That's a shame, because it's a fantastic manga that deserves to be rediscovered. This is a comic that has something to say about what it means to be human, and what it means to be alive. And it looks good doing it.

discuss this in the forum (9 posts) |