House of 1000 Manga

Gogo Monster

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

I know childhood isn't magical, because when I was four years old I told myself so. I made a point of burning a message into my brain: Adult self, don't go thinking children have any insights or magical perceptions, because we don't. That message is one of my earliest memories, along with a memory of scribbling with crayons and realizing I could never come up with anything truly original because even the most fantastic ideas were based on things perceivable in the real world. A unicorn was just a horse plus a horn, after all.

In retrospect, I was kind of a grim kid.

But even for me the trees had faces, and our apartment building was a castle with a tower that rose to greet us every time we pulled into the parking lot. My parents might pack up and leave while I was in the bathroom, leaving me alone forever, except for the invisible rabbit named Shaenon who lived in my mouth. It wasn't magic. It was just another way of seeing, one that gradually faded into something else. Maybe around the time I got glasses.

Taiyo Matsumoto, the great alt-manga artist, is fascinated by the way children see the world. In Japan he's probably best known for his (untranslated into English) surprise hit Ping Pong, still the greatest sports manga about table tennis. In the U.S. his most famous work is Tekkon Kinkreet, also published as Black and White, a trippy urban fantasy about two street kids fighting off yakuza in a futuristic megalopolis. Over time, his approach has shifted from surrealistic fantasy to psychological exploration and greater realism, but his theme is almost always the same: children scrabbling through a beautiful, hostile world built by and for adults, trying to make sense of it all and still maintain a sense of self.

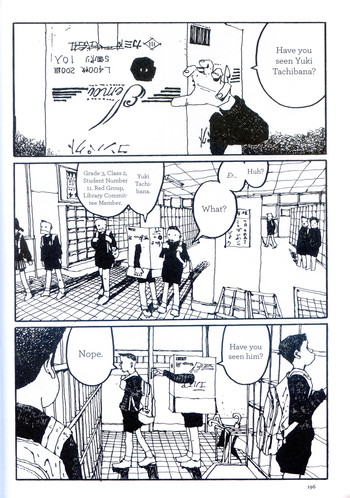

GoGo Monster stands halfway between Matsumoto the surrealist and Matsumoto the biographer of childhood. The narrative, though dreamlike and sometimes hard to follow, centers on two elementary school boys who become unlikely friends. Rosy-cheeked Makoto is dead average, able to blend into classroom society without much effort, but instead befriends smart, shaggy, seriously weird Yuki. Yuki yells creepy non sequitors in the middle of class, obsessively draws monsters, and talks about an alternate dimension inhabited by “the Others” and a guardian he calls Super Star. He hangs out with the school gardener, an elderly man who seems to understand him. “Yuki isn't the first,” he tells Makoto, who doubts that the things Yuki sees are real. “The things they've told me are surprisingly similar. The unseen ones love mischief…but they never cross a line.”

Rounding out the central cast is a third boy, IQ, the most brilliant kid in school. IQ represents down-to-earth rationality in opposition to Makoto's increasingly disconnected flights of fancy. He also refuses to take exams, spends his time tending the school rabbit hutch and obsessing over a favorite all-white bunny, and wears a cardboard box over his head at all times. If you can handle a manga where kid with a box on his head is the voice of reason, maybe you're ready for GoGo Monster.

The plot is simple enough, boiled down. Yuki doesn't want to grow up and lose his connection to the spirit world—or maybe it's really the world of his childhood imagination—so he retreats from physical reality, losing himself in fantasy and becoming more and more erratic. Makoto offers him friendship, IQ psychoanalysis. But the pull of the other world is strong, and eventually Yuki climbs the stairs to the school's nonexistent fifth floor, where the Others live. Maybe this is the only way to correct the imbalance of power between the human world, the Others, and Super Star set off by Yuki's arrival, an imbalance that eats at every living thing in the area. The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned. Or maybe it's all in Yuki's mind.

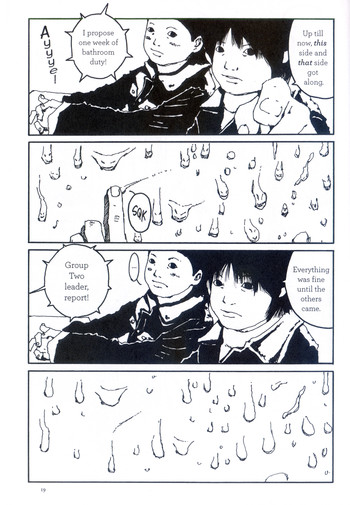

Matsumoto tells this simple-enough story with bizarre and beautiful imagery: blooming flowers, talking dogs, impossible landscapes, death, flight. GoGo Monster is most remarkable for its ability to show the everyday world as children see it. Every drop of water trickling down a window contains a face. Every airplane that flies over the school seems inches away. Adults mouth incomprehensible threats and corpses lurk under flowerbeds. Matsumoto remembers what it was like to navigate the world of childhood. And he remembers what it was like a little later on, when some kids made the leap into puberty and others lagged behind, and how confusing and embarrassing and painful that was. And how sometimes the things other kids talked about just seemed so dumb.

I know a lot of manga fans who didn't get into the story of GoGo Monster but enjoyed it anyway just because it's so gorgeous to look at. Matsumoto is an artist's artist, one of those guys who makes everyone else look bad without seeming to try very hard. He sketches his worlds in bold, loose lines that conceal surprising detail. He's good, scary good. Hell, some of my otaku friends confess they've never understood one of Matsumoto's stories but buy all his books just to look at them. And that's perfectly legit. (Can I mention that the slipcovered edition from Viz is a work of art? Because it is. Yowza.)

But the story of GoGo Monster did touch me, more than I expected. I'm cynical about stories about the magic of childhood, because I told myself to be. But Matsumoto captures something vital in this beautiful, unsettling one-volume graphic novel: something about the freedom of thought you have as a kid, and how growing up constricts that freedom, and one day childhood says you don't have to go home but you can't stay here. And that's when you have to choose what kind of adult you're going to be.

I think I know what happens in the surreal, Lynchian final pages of GoGo Monster. I think Yuki tries to return to the world he could access in childhood, but descends instead into the hall-of-mirrors depths of his own mind. What happens next is a triumph or a tragedy, or maybe both. I would like to message my younger self back with my opinion, but the lines of communication only go one way.

discuss this in the forum (5 posts) |

this article has been modified since it was originally posted; see change history