House of 1000 Manga

Summit of the Gods

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

Jiro Taniguchi is an artist who hasn't made nearly as many appearances in the House of 1,000 Manga as he could. Jason Thompson discussed his blissfully plotless Walking Man a million years ago, he has a story in Japan as Viewed by 17 Creators, and is that really the only Taniguchi manga we've covered? A prolific manga-ka churning out fine-lined, ultra-detailed depictions of stoic manliness since the 1980s, Taniguchi is probably the seinen artist most widely published in English. A good cross-section of his work is available in translation, although you may have to hunt around to find, say, the long-out-of-print 1990 Viz edition of Hotel Harbor View.

Taniguchi's subject matter ranges from hard-boiled noir to historical fiction to autobiography to, er, walking, but his protagonists are immediately recognizable: salt-of-the earth men in their thirties and forties, with solid builds and mild, hangdog faces. Taniguchi himself looks a lot hipper/nerdier than his characters, so maybe he's drawing his typical reader, a salaryman cracking open an issue of Business Jump for a much-needed escape from reality.

Much of the Taniguchi work in translation comes to us from Fanfare / Ponent Mon, a European coproduction born out of the Nouvelle Manga comics movement. Fanfare, the English-language half, is basically one person, Englishman Stephen Robson, who, fortunately for the English-speaking world, has excellent taste in manga. Without Robson's efforts, would we be able to read manly mountain-climbing manga like Taniguchi's Summit of the Gods? I don't think so.

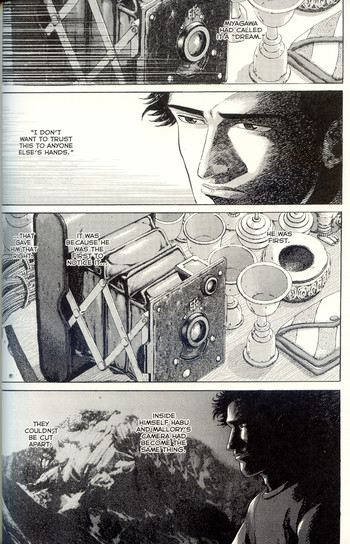

Based on a novel by Yumemakura Baku, Summit of the Gods wisely doesn't start with the mountain-climbing. Instead we're introduced to Makoto Fukamuchi, an outdoorsy photojournalist who discovers the story of a lifetime: an antique camera that may have survived George Mallory's legendary, doomed 1924 assault on Mount Everest. If the camera really belonged to Mallory, it'd change mountaineering history. But is it the real deal? And if so, how did it get from the top of Everest to a junk shop in Kathmandu?

Chasing the story, Fukamachi finds himself in pursuit of another mountain climber: Jouji Habu, a grimly determined, perpetually bestubbled man (a rare square-jawed departure from Taniguchi's usual whey-faced heroes) who conquered some of the world's most difficult climbs before disappearing from the face of the Earth. Fukamachi becomes convinced that Bikha Sanp (“Venomous Snake”), a Nepalese climber spoken of in whispers, is none other than Habu, and with the help of Habu's steely ex-girlfriend he sets out for the Himalayas. Along the way he records stories from Habu's friends and rivals (Hasu, another top Japanese climber, figures prominently in the early volumes before disappearing from the story), fellow mountaineers, and seasoned sherpas, turning the narrative into a sort of vertically-oriented Citizen Kane.

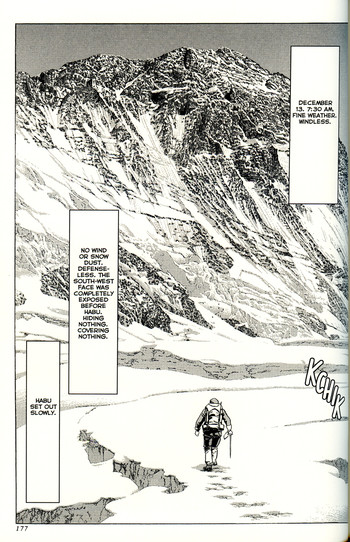

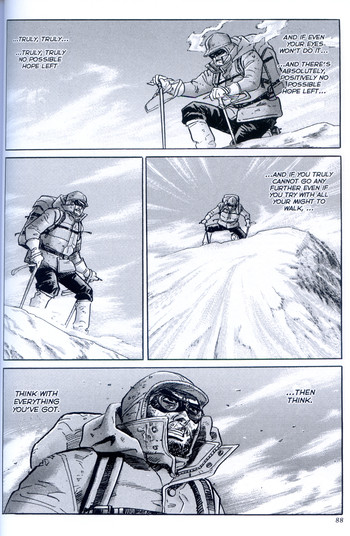

The mountain-climbing scenes start near the end of Volume 1, and they're spectacular. Taniguchi is evidently an outdoorsman himself, and he lavishes his trademark detail on sweeping mountain vistas and intense action sequences. We see climbers scale sheer cliffs, trudge through blizzards, bivouac in snowy passes, fall from nauseating heights, and hallucinate as they slowly freeze to death. They hear phantom voices call them to their deaths and see eerie mirages like a train of silent women in kimonos. They also revel in the most spectacular views on the planet and ascend to a world of extreme danger and heroism that doesn't exist down at sea level.

After a while, you start to wonder why they do it. A lot of characters die on those mountains, and for what? Mallory is the climber who famously answered the question with, “Because it's there,” and Summit of the Gods returns to that idea again and again. In a sense, mountain climbing is the purest form of achievement: doing something difficult not to create or discover or leave behind any tangible contribution to society, but simply for the sake of doing it. As sophisticated as the storytelling can get—we delve into the complexities of the characters’ relationships and learn about nuanced issues like the treatment of Nepalese sherpas by glory-seeking foreign climbers—at its core Summit of the Gods is an old-fashioned, red-blooded, cheer-for-the-champions shonen manga. At least it has the “effort” and “victory” parts of the hoary Shonen Jump “friendship, effort, victory” formula sewn up.

There's also the appeal of machismo, of course. Again and again, Fukamachi is reduced to weak-kneed awe by Habu's rugged feats and laments his own middle-class Japanese softness. (I really hope there's some Summit of the Gods yaoi out there, if only to take advantage of lines like, “A beast with an unsated hunger. It lay concealed inside Fukamachi. A beast called Jouji Habu.” HOT.) Habu himself isn't much of a philosopher. “A mountaineer is a mountaineer because he climbs mountains,” he says. “He doesn't climb to die. If you die…you're nothing.”

A lot happens in the five fat volumes of Summit of the Gods. Love, death, kidnappings, cars flying off cliffs, warring gangs, a mysterious jade necklace, the history of Nepal, and endless mountain climbing lessons. We learn how to acclimate to limited oxygen, what to eat on the peaks, how to tell you're losing fingers to frostbite, and how to chain yourself to the side of a cliff while the ghosts of lost climbers hover around taunting you. The mystery of the camera drives the plot, but any story about mountain climbing is ultimately a story about obsession, and inevitably Fukamachi starts to become as driven to climb as his elusive subject. Eventually, it's clear there's only one way this story can end: with Fukamachi and Habu teaming up to take Everest. But by that time, just climbing the tallest mountain on Earth isn't quite manly enough for the likes of Habu. Is there any way they can make it a real challenge?

This manga will put hair on your chest. It may or may not make you want to climb mountains, but you'll want to cowboy the hell up and do something super badass just to prove to yourself that you can. I've never read a Taniguchi manga that wasn't stunning to look at and stirring to read. Even Walking Man made me want to be a better walker. As Jason Thompson taught us a couple of weeks ago by reading all of Naruto in one sitting, sometimes you have to push yourself beyond the limit. Because it's there.

discuss this in the forum (10 posts) |