House of 1000 Manga

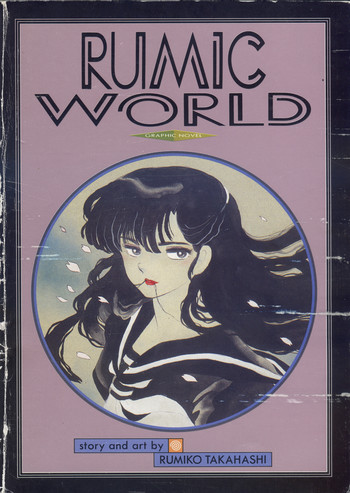

Rumic World & Rumic Theater

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

When I think of the comics that floored me as an impressionable young nerd, the ones that got me obsessed with what this mongrel art form can do, I think of a lot of the acknowledged heavy hitters. Maus. Understanding Comics. Phoenix. The works of Lynda Barry and Moto Hagio. But there are also the outliers, the wild cards, the odd little comics that happened to hit me at just the right time.

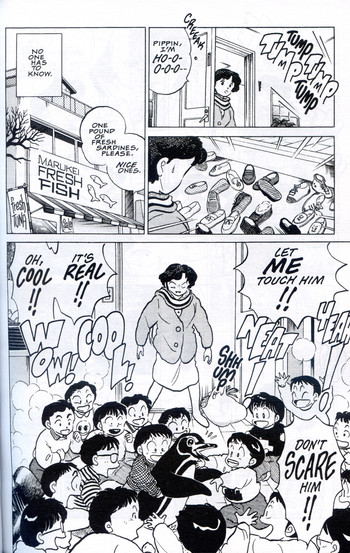

So I remember the first time I read Rumiko Takahashi's short story “The Tragedy of P,” a feather-light comedy about a family in a no-pets apartment that takes in a tame penguin. Anyone who's read Takahashi's manga—and who in the manga-reading world hasn't?—knows what to expect from this setup: wacky hijinks with cute animals, and possibly also kids. And that's exactly what happens. But midway through the story, the mother of the family takes the penguin out for a walk at night and ruminates on the cruelty of keeping an animal cooped up in a tiny apartment, even out of love. “The sky, the stars, the wind and the light are yours,” she thinks as the penguin gazes up into the infinite night. “They are not ours to give you. Or to take away.” With that two-page spread I realized that even a silly comic-book sitcom could strive for beauty, and something about the way I did comics changed forever.

I read “The Tragedy of P” in Issue #1 of Manga Vizion, the first of many manga anthology magazines published by Viz, which ran from 1995 to 1999. Through most of its run, Manga Vizion continued to publish Takahashi's short manga, which Viz then reprinted in paperback collections under the title Rumic World and, later, Rumic Theater. Takahashi still draws short comics every once in a while, and her publisher, Shogakukan, prints them in whichever of its magazines seems most appropriate. Publishers know they can count on Takahashi for solid, crowd-pleasing genre entertainment. And, every once in a while, for magic.

The Rumic World and Rumic Theater collections, now all long out of print, are lots of fun. Although Takahashi's work seldom strays too far outside a certain range of upbeat, anime-ready charm (many of the Rumic stories have been adapted into animation), her short pieces show off what turns out to be an impressive range of storytelling skill. She tackles science-fiction, fantasy, horror, comedy, sports, and little dramas of contemporary life.

Some of the stories tread the same ground as Takahashi's longer, better-known series. “Maris the Chojo,” a rollicking comedy starring a super-strong, bikini-clad space mercenary and her nine-tailed alien fox sidekick, bears a strong resemblance to Urusei Yatsura, which had launched two years earlier. The superb time-travel romance Fire Tripper, in which a high-school girl finds herself in feudal Japan with a surly young warrior to protect her, shares elements with the much-later Inuyasha. “Excuse Me for Being a Dog!”, about a teen martial artist who transforms into a dog when his nose bleeds, reads like a dry run for Ranma 1/2, and would even if the female lead didn't look and act exactly like Ranma's OTP, Akane Tendo.

Some of the stories tread the same ground as Takahashi's longer, better-known series. “Maris the Chojo,” a rollicking comedy starring a super-strong, bikini-clad space mercenary and her nine-tailed alien fox sidekick, bears a strong resemblance to Urusei Yatsura, which had launched two years earlier. The superb time-travel romance Fire Tripper, in which a high-school girl finds herself in feudal Japan with a surly young warrior to protect her, shares elements with the much-later Inuyasha. “Excuse Me for Being a Dog!”, about a teen martial artist who transforms into a dog when his nose bleeds, reads like a dry run for Ranma 1/2, and would even if the female lead didn't look and act exactly like Ranma's OTP, Akane Tendo.

But some of the strongest Rumic stories are the non-supernatural (or maybe just slightly supernatural) dramas. In addition to “The Tragedy of P,” which will forever hold a special place in my heart, the standouts include “The Merchant of Romance,” about the travails of a young divorcée operating a run-down wedding chapel, and “To Grandmother's House We Go,” in which a woman and her boyfriend plot to falsely claim a deceased friend's inheritance (the rightful heirs are murderous jerks, though, so it's totally okay). Takahashi is also surprisingly good at horror, in spite of her cheery art style. “The Laughing Target,” one of her early stories, is an effectively creepy tale about a beautiful girl who sends swarms of ravenous…things…to devour those who cross her.

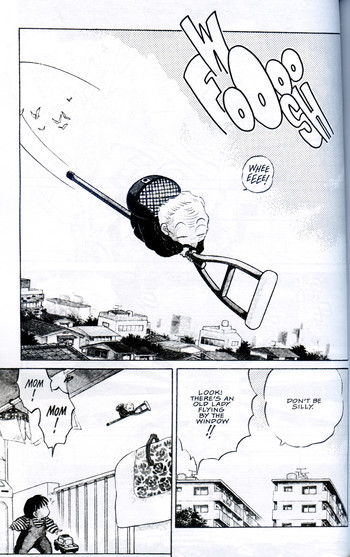

Some of the stories feel like pilots for series that never happened. Takahashi seems to be a bottomless font of high-concept premises that may or may not be capable of supporting an ongoing comic. I'd read a continuing series about the struggling wedding chapel, but I'm not sure I'd be able to maintain interest in, say, a yam-gardening youth leader's ideological battle with a bodhisattva (“Shake Your Buddha,” one of many cases where the Viz translation team took merry license with the Japanese title). Ah, but what about a telekinetic old woman who rides through the skies on a flying crutch (“One Hundred Years of Love”)? A dead kendo coach who possesses a teenage girl so he can continue to train his star swordsman (“One or Double”)? A rugby team with a ghost cheerleader (“Winged Victory”)? These concepts may sound far-fetched, but are they any weirder than a lightning-powered alien demon girl, a time traveler teaming up with a dog demon, or a martial artist who changes sex when s/he gets wet? Maybe, but not by much. You can never predict where the next hit will come from, and in her early days Takahashi chose to throw everything at the wall until something stuck.

Yet the stories aren't slapdash; even the earliest entries are polished, confident, and well-plotted, the characters sketched into place with sure strokes. Takahashi studied manga through the Gekiga Sonjuku, a program started by Lone Wolf and Cub creator Kazuo Koike in the 1970s, which focuses on building character-driven plots. “If you have a strong character,” Koike told Carl Gustav Horn in a 2006 interview for Dark Horse, “the storyline will develop naturally, on its own. The storyline then follows in the character's wake, and swirls around the character, influencing the character further...Strong manga can only be made when you create a strong character.” Takahashi's work seems a million miles away from Koike's ultra-macho seinen thrillers (though I'd love to see any Takahashi character quote Wounded Man: “Blood got in my eyes and I can't see a damn thing! Piss on me so that I can wash it off!”), but she took his advice to heart. Every Takahashi story is propelled by its characters.

That's what struck me, reading “The Tragedy of P” years ago. A lesser cartoonist, writing a silly situation comedy, would focus on the situation. A better artist steps back to consider the people in that situation, their thoughts and feelings. To see the woman kneeling in the gutter, and the penguin looking at the stars.

discuss this in the forum (6 posts) |