House of 1000 Manga

Ten Cent Manga

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

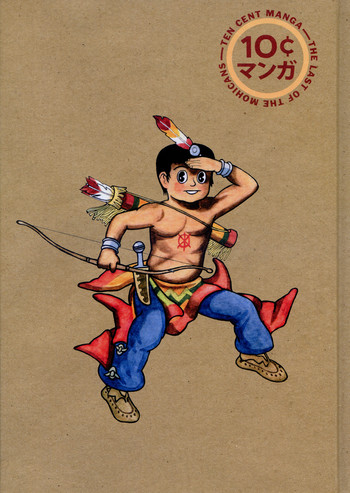

Ten Cent Manga

Indie art/music/comics publisher PictureBox closed its doors in December of last year. It was a blow to fans of out-there American comics like the Art Out of Time anthologies of bizarre vintage comic books or the work of multimedia art collective Paper Rad. But it was also a sad day for manga, because PictureBox put out some cool, bizarre stuff. PictureBox's manga line included Seiichi Hayashi's classic gekiga Gold Pollen and Other Stories and The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, the first collection of bara, or gay men's manga, released in English. (A planned follow-up bara anthology, Massive, was picked up by Fantagraphics after PictureBox folded.)

Just before its demise, PictureBox launched its coolest manga project yet: Ten Cent Manga, a line of early postwar manga from the era before Osamu Tezuka changed the way everyone in Japan drew comics. I love weird old pulp manga. I love unquestionably great old manga too, like Noboru Ōshiro's wartime trilogy of graphic novels for children. But there's a gritty fascination to the less-classy stuff from the period as well, the titles that sold in manga rental shops because they were too violent or badly drawn for respectable children's magazines and often appeared in ultra-cheap formats like paperback akahon (red books). Mere weeks ago, my co-columnist Jason Thompson consigned these cheapass old manga to Manga Hell, but he was wrong! So wrong! At the very least they should be lifted to Manga Purgatory, all the better to guide us to Heaven.

During its brief existence on this plane, the Ten Cent Manga line produced two books, Osamu Tezuka's The Mysterious Underground Men and Shigeru Sugiura's Last of the Mohicans. Neither is really representative of typical early pulp manga. Last of the Mohicans is actually Sugiura's own 1970s recreation of his original (and less interesting) 1953 manga, and YOU can't argue that a Tezuka manga is “typical” of anything but Tezuka. But man, are they weird.

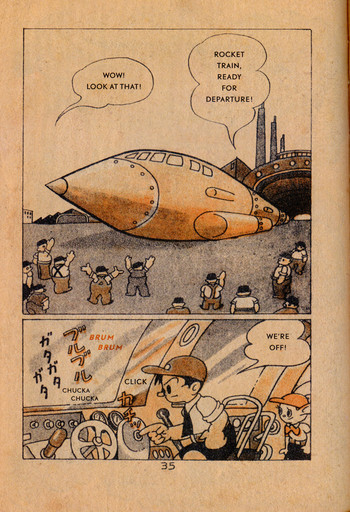

If you've read any early Tezuka, you know roughly what to expect from The Mysterious Underground Men: nonstop gung-ho action, sci-fi machinery, grimly heroic little boys in short pants, random bouts of slapstick comedy and tearjerking sentimentality, and a plot that jumps erratically from idea to idea as Tezuka keeps thinking of stuff he wants to draw. This is the oldest Tezuka manga available in English translation, so it's not surprising that in many ways it's the crudest (although Tezuka's super-early animation-style art is cute). The central plot involves an expedition through the center of the Earth via a sweet rocket car with a drill mounted in the nosecone. The explorers anger an underground civilization of termite people, whose queen bribes one of the less trustworthy members of the team (played by Ham Egg, one of Tezuka's early recurring “star system” characters) to betray humanity by blowing up buildings and sort of randomly messing with everyone.

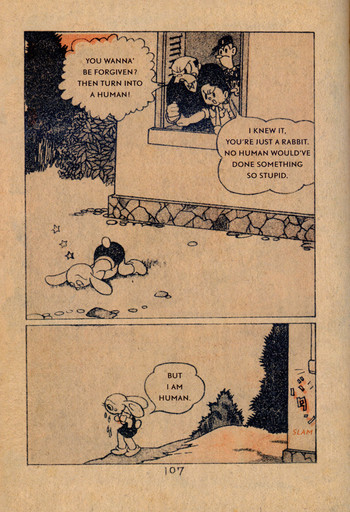

But the manga's most interesting element is a subplot following Mimio, an intelligent humanoid rabbit created by science (because why not, is why), and his efforts to be accepted as human. Mimio is the first of many Tezuka characters to explore the nature of humanity and the plight of minorities struggling for acceptance in society, and his surprisingly somber story arc (he is, after all, a cute cartoon bunny) moved many children in 1948. The Mysterious Underground Men was one of Tezuka's earliest manga efforts, and it seems to have been the first one he was really pleased with. He called it his first true “story manga” with a unified plot and developed characters.

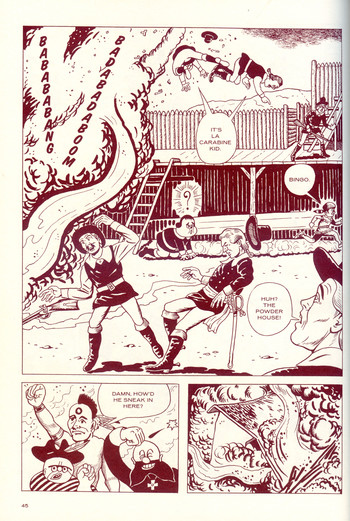

As pulpy as it is, The Mysterious Underground Men is a little too classy to give the reader a taste of true akahon flavor. For that, we need Last of the Mohicans. Anyone expecting a remotely accurate—or coherent—adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper's novel is in for a disappointment. The hero, who looks distractingly like Bob's Big Boy, is named Hawkeye, and the action is sort of set in colonial America, but from there it's Shigeru Sugiura's happening and it freaks him out. The plot is a red-blooded Western inspired by American cowboy movies, but set in a cartoony world where characters break the fourth wall and horses and bears talk back to people. The battle scenes are half realistic carnage, half people getting bonked on the head to wacky sound effects. The constant switching between action melodrama, slapstick gags, and winking anachronistic humor creates whiplash changes in tone that make Tezuka at his wackiest look sedate.

The art is a similar jumble of styles and tones, with doodle-y cartoon characters coexisting alongside realistic, square-jawed figures painstakingly copied from American comic books. Shigeru draws lovely landscapes, just not necessarily of colonial New England, where Cooper's novel takes place. Sometimes the characters are in the American Southwest of cowboy movies, and at other times Shigeru copies panels from the classic Jesse Marsh Tarzan comic, so America suddenly sprouts lush jungles and waterfalls.

Shigeru was one of the most popular manga artists of the postwar era, and his erratic storytelling and shameless lifting from other sources are typical of the period. In the 1970s, his work was rediscovered and gained a cult following in the gekiga movement. Shigeru recreated some of his old children's manga for Mushi Comics, the publishing wing of Tezuka's animation studio, and drew weird new stuff for indie magazines and gekiga publishers. Hipsters dug his work. Last of the Mohicans was put out by the publisher of Treasure Island, a pop-culture magazine that aimed to be the Japanese Rolling Stone. It's hard to tell how much is genuine old-school pulp and how much is knowing pop-art collage. Either way, it's a trip.

Manga like Last of the Mohicans and The Mysterious Underground Men probably appeal to a limited audience of hardcore manga scholars and connoisseurs. Fortunately, PictureBox realized this and released both in handsome hardcover editions packed with bonus information. The Mysterious Underground Men carefully reproduces the look of the manga as originally published (in color!). Both books include essays by the manga-ka; Tezuka's is on the history of Underground Men, while Shigeru's is on his favorite silent pulp movies. Comics historian Ryan Holmberg provides a lengthy essay on each manga, including an exhaustive breakdown of all the material Tezuka and Shigeru ripped off. (Tezuka lifted from Flash Gordon serials, Milt Gross's early graphic novel He Done Her Wrong, and a German novel called Tunnel—his manga is even still called Tunnel on its title page—while Shigeru was lifting from artists like Alex Toth left and right.)

Okay, these manga are not for everyone. Some people will look at them and give thanks that eventually Tezuka invented Astro Boy and manga artists stopped trying to draw clumsy pastiches of American comic strips and low-budget movies. But strange, forgotten old manga are my Kryptonite, and when some bold publisher puts out a nifty edition with tons of historical background to explain what the hell was going on in the manga-ka's mind when he came up with humanoid rabbits or Mohicans in the jungle, I can't resist. I'm only sorry PictureBox didn't get the chance to continue the line, because even at $24.95 a pop, Ten Cent Manga is a bargain.

discuss this in the forum (3 posts) |