House of 1000 Manga

Domu

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

Editor's note: things are changing at the House of 1,000 Manga! Moving forward, this will be a tag-team column, swapping off between Jason Thompson and Shaenon K. Garrity, who has written guest columns in the past. This week, Shaenon begins her stint as a regular with one of her all-time favorite manga.

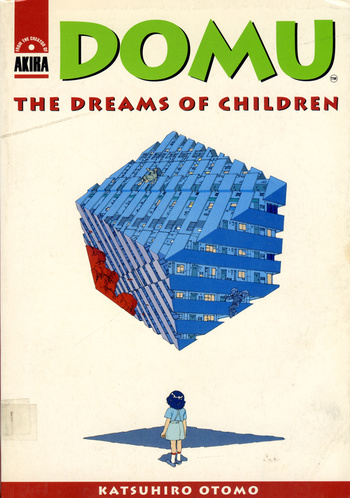

In the great haunted house stories, the house is a central character, whether it's Hill House or the Overlook Hotel or the house on Ash Tree Lane. There's also usually an element of the devil's bargain to the story: the protagonists grasp at the promise of a dream home (or, in the case of The Shining, a dream job—what frustrated writer wouldn't want to get paid to spend the winter in a luxury hotel working on his novel?), realizing too late that their real-estate bargain contains more than they bargained on. Part of the grim horror of Domu, Katsuhiro Ōtomo's first major manga, is that no one would choose to live in the anthill-like concrete apartment complex where most of the action takes place. When people start to die in increasingly suspicious “accidents,” those who can afford to move away do so, but few can. There are still hundreds of victims, trapped in their cramped apartments, for the consciousness haunting the neighborhood to toy with and pick off, one by one.

The apartment block, not sane, looms faceless over Domu, sometimes alien and menacing, sometimes an Escher-like maze, sometimes a fortress in need of a knight to defend it from the dragon. In the early pages of the manga, Otomo's art is sometimes stiff and generic, only showing glimpses of the genius that would someday draw Akira, but he never shies away from meticulous details of architecture and décor. He knows that the success of his story depends on his ability to make us believe in the reality of that apartment block. Or maybe, judging from the rest of his body of work, he just really, really likes drawing buildings.

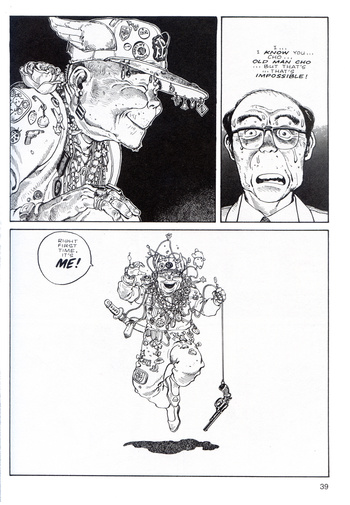

As it turns out, the block isn't haunted by a ghost, but by a powerful psychic presence. No one, least of all the confused cops investigating the epidemic of suicides and accidents, imagines that the killer is Old Man Cho, a senile old man who happens to possess immense psychic powers. (No explanation is ever given for the psychic powers in this story, and all we learn about Old Man Cho's history is that his family used to live with him but suddenly moved out some time ago…funny, that.) Old Man Cho is happy, a spider in an ant's nest, killing people for fun or to steal shiny trinkets. No one suspects him; a psychic brought in by the police refuses to go near the apartment complex once she gets a whiff of the aura inside. No one cares that much about the lower-class people living in the building, and the people are preoccupied with problems of own: alcoholism, unemployment, mental illness. Only the local children, maybe, sense the deep wrongness in the air.

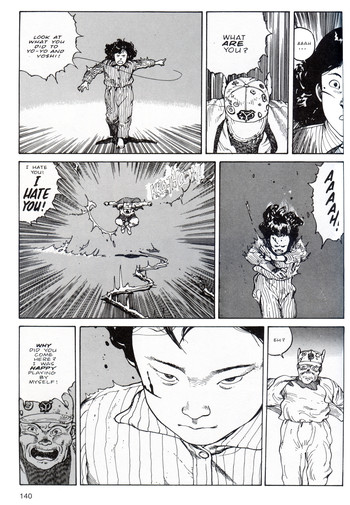

Then something happens. A new family moves into the block, with a little girl. One afternoon Old Man Cho, up to his usual tricks, telekinetically tosses a baby off an upper-story building. Instead of falling, the baby floats gently to the ground, and the little girl, Etsuko, marches up to the old man in a snit. “You're nothing but a bully!” she sniffs at him. There's another powerful psychic in the neighborhood, and the battle between old evil and young justice begins.

In many ways, Domu is a test run for Otomo's undisputed masterpiece, Akira, with its similar themes of psychic powers and generational conflicts, its similar imagery of buildings exploding and bodies twisting in hyper-realistic detail. But I like Domu better. One thickish volume long, it's spare and direct, trimming its story down to the essentials. The depiction of neighborhood-flattening psychic powers is imaginative but strangely plausible. In his memoir Moeru America, Viz founder Seiji Horibuchi lists Domu among the titles that got him into manga in the 1980s—partly because it reflected his own New Age beliefs in ESP and the supernatural. As it happened, Viz never published Domu, probably because other publishers got to it first; it was first published in English in 1994 (the edition from which these flopped, hand-lettered scans were taken), and has since been reprinted by Dark Horse.

By restricting its conflict to a single group of people in an apartment complex (and an equally foreboding city hospital), Domu, unlike Akira, never loses sight of its human element. Every death hits hard. Etsuko, who is courageous and powerful but still, when push comes to shove, a little girl, is one of the most remarkable child characters in manga. She isn't cute and she isn't fooling around. She is as solemn as a child at play. Otomo's drawings of children, their expressions and body language, are amazing throughout the manga. This is another area in which, even as a young and sometimes uneven artist, he draws with absolute surety. Very few artists draw children well, but Otomo's children are almost frighteningly natural.

Because it's only one volume long, Domu has room for only one all-out Akira-style psychic battle, with billowing explosions and shattering windows and people flying through the night air. It's gorgeously executed, giving no doubt that readers are looking at the emergence of a science-fiction master. But then Otomo does something fiendishly smart: he follows his firework climax with another battle between Etsuko and Old Man Cho, one that takes place almost entirely inside their minds and is as subtle as the previous battle was theatrical. Stephen King played a similar trick in his first major work, Carrie, following the bloodbath at the prom with the quiet, and in many ways far scarier, confrontation between Carrie and her mother.

Domu ends on a nearly wordless 24-page sequence in which almost nothing, externally, happens, but it's more tense than anything that's come before. It's one of the best pieces of comics storytelling ever drawn. Otomo at the beginning of Domu is a very good cartoonist, but by the end he's one of the geniuses of the form. Countless manga artists have imitated his hyper-detailed art style, but few have touched his ability to tell a story in pictures.

After Domu, Otomo drew Akira, of course. He never went on to be a prolific artist, mostly swapping time between shorter manga and animation projects—and, more recently, directing the live-action film adaptation of Yuki Urushibara's Mushi-Shi. He clearly works only on projects that deeply interest him for one reason or another, which, given the amount of effort and detail he lavishes on them, is understandable. But when he wants to, he can build a world brick by brick—a world of horror and wonder and the darkest of children's dreams.

Shaenon K. Garrity is an award-winning cartoonist best known for the webcomics Narbonic and Skin Horse. Her prose fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons, Lightspeed, Escape Pod, and Daily Science Fiction. Her writing on comics appears regularly in The Comics Journal and Otaku USA. She lives in Berkeley with two birds, a cat, and a man.

discuss this in the forum (11 posts) |