House of 1000 Manga

Phoenix

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

The artistic direction of American comics was shaped by a number of key figures: Charles Schulz, Winsor McCay, Will Eisner, Jack Kirby. But in Japan, it's all about Osamu Tezuka. (Well, maybe Tezuka flanked by the shojo artists of the Year 24 Group, who invented most of the tropes Tezuka didn't.) Tezuka combines elements of all the great American innovators. Like Schulz, he built an industry on simple, deceptively nuanced characters. Like McCay, he drew obsessively (both men died pleading for the chance to keep drawing) and was an early adopter of animation as a sister art form. Like Eisner, he was a tireless champion of comics as serious art and, later in life, supported a new movement toward comics for adult audiences. And like Kirby, his greatest work is simultaneously brilliant, innovative, and batshit insane.

So it is with Phoenix, Tezuka's unfinished twenty-year epic and one of his masterpieces. It's not just great because it's filled with memorable characters, ambitious ideas, and stunning visual storytelling. It's also great because it's not afraid to be nuts. It's got some of the best of Classy Tezuka, the auteur who gave us a multi-layered World War II drama and a biography of the Buddha, and also some of the best of Batshit Tezuka, the guy who had Black Jack operate on his own intestines while surrounded by dingoes in the Australian outback.

Tezuka intended Phoenix to be his magnum opus, and he cleverly builds in a structure open enough that he can include virtually any type of story he feels like drawing at a particular time. The manga consists of a series of stories that move back and forth through time: the first takes place in the distant past, the second in the distant future, the third in the slightly less distant past, and so on.

Initially, the stories seem to be connected only by the presence of the Phoenix, the immortal and enigmatic firebird, who appears in every story in some form. Gradually it becomes evident that some characters are being reincarnated into multiple eras, especially Saruta, a squat, lumpy-nosed man who frequently shows up either committing or atoning for some sin, never quite advancing along the karmic wheel. In the later volumes, other characters recur and the time streams start to cross, suggesting an eventual climax in which past and present meet.

But if Tezuka planned such a climax, he never reached it. At the time of his death in 1989, he was still working on Phoenix. He left behind an outline for a volume entitled “Earth,” set in China in 1938, but the ending of the series is destined to remain unknown. Instead, we have twelve stories, ranging from science fiction to fantasy to historical drama, exploring—sometimes profoundly, sometimes goofily—themes of life, death, and eternity.

(Note: I'm covering the stories in chronological order as Tezuka wrote them; the English edition from Viz orders them somewhat differently, probably because some of the stories are of awkward lengths for book collections. The Viz run also includes Early Works, a collection of manga featuring the Phoenix character in different historical settings that Tezuka drew before beginning Phoenix proper.)

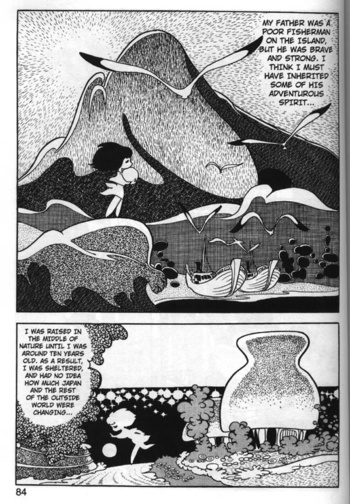

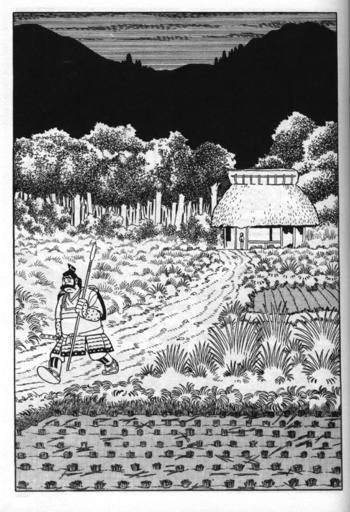

Story #1: Dawn (1967)

Japan, third century A.D. Nagi and his sister Hinako are the only survivors when their tribe is wiped out by their warlike neighbors. While Nagi lands under the heel of the vain priestess/queen himiko, Hinako marries one of the invaders and hides out in the wilderness, trying to rebuild her tribe in the most direct way possible. Ultimately, Nagi is sent out to hunt the Phoenix for Queen himiko, who wants to drink its blood for eternal youth, something rulers are constantly trying to do in this series.

Tezuka bases the setting on the scanty information available about Japan's prehistoric cultures (the earliest written mention of Japan is a first-century Chinese record that describes it as a country ruled by a queen.) Some of the characters and details are based on Shinto mythology, especially Hinako, who resembles the sun goddess Amaterasu. As often happens in Tezuka's work, the plot wanders as the artist keeps thinking of new things to draw and new situations to get his characters into. There's ambition here, but this is primarily a warm-up piece, giving Tezuka the chance to play around with ideas he'll explore at greater depth later.

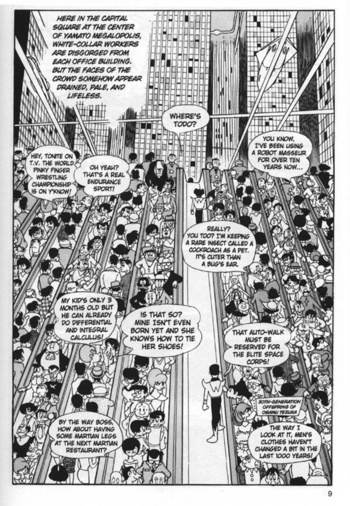

Story #2: Future (1967-68)

Earth, 35th century. Humans live in high-tech, overcrowded indoor cities, distanced from the natural world and from each other. Typical 35th century man Masato acquires a “Moopie,” a shapeshifting alien that humans raise as perfect companions, which takes the form of a beautiful woman. Masato falls in love with his Moopie, which is forbidden in his society (although you'd think it would happen a lot), and the two flee their city as civilization collapses around them. In the barren wastelands, they run into Dr. Saruta, a mad scientist trying to create artificial life and start the world anew.

Tezuka is getting into his groove here. All life on Earth is destroyed halfway through the story, and it just keeps going. That's the outrageous scope that makes him the God of Manga. The romance between Masato and the Moopie is unconvincing, as Tezuka's sappier love stories tend to be, but the vast Metropolis-style cities and apocalyptic sequences of destruction provide an appropriately operatic backdrop to what is, at least in Phoenix chronology, the end of time. When Viz first published Phoenix, it started with Future as a kind of test run, banking that it was impressive enough to get people excited about the rest of the series.

Story #3: Yamato (1968-69)

Japan, fourth century. A sweeping depiction of the conflict between the Kumaso, one of the native cultures of prehistoric Japan, and the invading Yamato, ancestors of the modern Japanese. The pacifist Yamato prince is sent to capture the Phoenix by his warlike father, who, like Queen himiko in “Dawn” and many, many other people throughout the series, is obsessed with immortality. The prince teams up with a Kumaso warrior woman and learns to approach the Phoenix peacefully, but elsewhere war erupts, and the Yamato king gets busy planning to bury hundreds of his subjects in an enormous tomb.

This is one of the strongest of the historical war epics in Phoenix, contrasting bloody battle scenes with delicate, impressionistic sequences of the prince's efforts to commune with the Phoenix through music. Ultimately, it's a story of pacifism and self-sacrifice, reflecting the Buddhist philosophy that permeates the series even when the characters technically predate Japanese Buddhism.

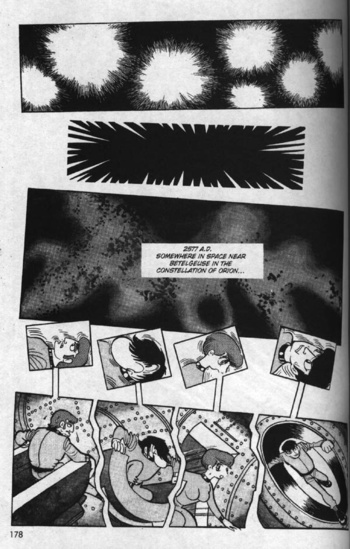

Story #4: Space (1969)

Deep space, 26th century. One of the most visually innovative entries, “Space” starts as a murder mystery set in deep space, although, Tezuka being Tezuka, it drifts off on weirder and weirder tangents. Four space travelers awaken from cryonic sleep to find their ship damaged and the pilot dead. Fleeing in separate escape pods, they communicate with each other over radio for as long as they remain in range. Eventually the truth about their dead crewmate comes out, and the story moves on to distant planets and an alien Phoenix.

The most remarkable section of “Space” is the lengthy escape pod sequence. Striking page layouts line the characters up, then shake them out of place as their relationships and psychodramas rise to the surface. It's a masterful way to give visual intensity to a mostly static situation. Even by the high standards of Tezuka's mature period, this is a great-looking comic.

Story #5: Karma (1969-70)

Japan, eighth century. The story follows two men whose paths keep crossing throughout their lives: Akanemaru, a gentle Buddhist scholar, and Gao, a bitter, deformed bandit. Both men ultimately become artists, and both experience religious visions of the cycle of reincarnation. Akanemaru's art wins fame and respect, but he recognizes that Gao, who channels his rage into brilliantly ugly sculptures, is the superior talent. Then both men are recruited to work on the construction of an ostentatious temple to the Buddha, which represents the antithesis of the Buddhism in which they believe.

“Karma” is a spectacular work: not just the best installment of Phoenix, not just one of the best things Tezuka ever drew, but one of the greatest graphic novels of all time. It's gorgeously drawn, with spectacularly detailed landscapes and riveting action. The overarching story is strong but also makes room for bravura individual sequences like a long passage in which Akanemaru, meditating before a portrait of the Phoenix, has a vision of being reincarnated over and over as different animals. And yet there's also space for out-of-left-field Tezuka nuttiness like a subplot about a ladybug that falls in love with a human. If you read only one volume of Phoenix, read this one.

Story #6: Resurrection (1970-71)

Earth, 25th century. The story begins like Astro Boy, with a young man dying in a car accident. Resurrected by doctors, he returns with a strange mental condition that causes him to see other people as inanimate objects. One day he catches sight of what he perceives as a human being—but to everyone else she's a robot. Oh, it gets weirder. Cut to a moonbase 500 years later, where the last robot of the malfunctioning “Robita” model waits on a solitary creep (played by Tezuka “star system” cast member Acetylene Lamp) who prefers to live surrounded by a staff of obedient machines. The narrative flashes back and forth between the two storylines until they come together in a final twist.

I love this extremely weird story. It's got psychedelic love scenes, body-swapping technology, people appearing as piles of rocks, and a robot lying facedown on the surface of the Moon shouting, “God! Forgive-me-for-my-sins!”—and you know what? It's also genuinely touching. On the other hand, it has almost nothing to do with the Phoenix, and this is one of several cases, especially with the sci-fi stories, where one suspects Tezuka just retooled an unrelated story he had lying around to fit it into the Phoenix mythos.

Story #7: Robe of Feathers (1971)

Japan, tenth century. The shortest installment of Phoenix, this is a retelling of the Japanese folktale “The Heavenly Maiden's Robe” with a sci-fi twist. As in the folktale, a man happens upon a celestial spirit bathing and steals her robe, which forces the spirit to become his wife. The nifty device here is that Tezuka presents the story as a stage play, with the reader facing a fixed stage decorated with stylized props. There's even stage lighting and sound effects. The Phoenix doesn't play much of a role, but it's a beautiful little story.

Story #8: Nostalgia (1976-78)

Space, 25th century. A young couple colonizes the distant planet Eden 17, but the husband dies, leaving the wife, Romy, to raise their baby and pick up badass survival skills. She comes up with a plan to populate the planet: she will put herself in cryonic sleep, awakening once a generation to bear children with her male descendents. As solid an idea as this may seem, the situation becomes untenable, so the Phoenix steps in and introduces Moopies to the planet. Eventually a society of Moopie-human hybrids arises…and we're still only halfway through, as Romy and one of her Moopie descendents leave the planet and encounter still stranger worlds.

Even by Tezuka standards, this is a weird one. It's a lot of fun, provided you can stomach the incest plot, but it wanders all over the place and is mostly an excuse for Tezuka to play with a long string of wild ideas. It's filled with Old Testament references, making it sort of the Judeo-Christian entry in Phoenix’s survey of religious themes and imagery. So, Christians, this is what Tezuka thought best represents your religion. (Come to think of it, the freezing-yourself-so-you-can-rule-your-descendents concept is also central to Orson Scott Card's Worthing Saga, so maybe this is specifically the Mormon chapter of Phoenix.)

Story #9: Civil War (1978-80)

Japan, 12th century, the end of the peaceful Heian Period and the beginning of an era of civil war. Benta, a none-too-bright lug of a woodcutter, travels from his rural home to Kyoto, the capital of Japan, in search of his kidnapped fiancée Obuu. Obuu has been sold into the household of Kiyomori, the corrupt old head of the Taira clan, where she becomes his trusted aide. Meanwhile, Benta is swept up in the massive war brewing between the powerful rival clans of Kyoto.

This is a long story, covering almost two full volumes in the Viz edition. It's basically an expanded and improved version of “Dawn,” with similar plotlines and themes handled in a more sophisticated, more beautifully drawn way. It even mirrors the references to Shinto deities in “Dawn” by basing many of its characters on semi-historical Heian figures: Benta is the legendary warrior monk Benkei, and the first manga artist makes an appearance. The story drags sometimes, but Tezuka is clearly having fun drawing Heian stuff and incorporating imagery from art of the period: ghosts and demons, animals, detailed battle scenes, views of Mt. Fujii. When war finally breaks out, it's depicted spectacularly. Also, a surprising amount of space is devoted to monkey fights.

Story #10: Life (1980)

Japan, 22nd century. A TV producer pitches a reality show around hunting human clones and recruits a scientist to unlock the secret of life (something that was still befuddling people in the 33rd century, back in “Future”). Together they go looking for an Incan ruin said to be inhabited by a bird woman who can create life. Eventually the TV show does get made, but, as usual, that's just the halfway marker before Tezuka veers off in a whole other direction.

Similar in tone to Tezuka's adult-oriented work of the period like MW, this is a bleak story, and to my mind one of the less successful installments of Phoenix. The sci-fi, fantasy, and satirical elements don't quite mesh successfully—the trip to the Incan ruins feels especially out of place—but at least Tezuka keeps coming up with creative ways to incorporate the Phoenix into the futuristic settings.

Story #11: Strange Beings (1981)

Japan, 15th century. A nifty time-loop story based on the legend of Yao Bikuni, a Buddhist nun said to live for 800 years. Sakon Suke, a noblewoman disguised as a samurai, kills Bikuni and finds herself trapped on the nun's isolated island, where time flows strangely. She takes over the duty of healing the sick, including parades of monsters and spirits who show up at Bikuni's doorstep. Eventually, she encounters the Phoenix and learns that she's become part of an endless cycle of sin and penance.

This is another of my favorite Phoenix stories. The time paradox is predictable, but the story unfolds engrossingly, and Sakon Suke and her faithful manservant—who's remarkably cool about getting stuck on a freaky island with her—are some of the best characters in the series. It's one of the stories that best expresses Phoenix’s recurring theme of Buddhist cycles of fate. Also, Tezuka draws a lot of boss monsters.

Story #12: Sun (1986-88)

Earth, seventh century and 21st century. The timelines cross! In the Aftermath of a battle, Yamato soldiers skin the face of a fallen soldier named Harima and replace it with the face of a dog. (Which, yes, weird, but Tezuka's Ode to Kirihito has a similar premise, so dog-faced men must have been a thing with him.) Rescued by an old medicine woman, Harima joins the Spirit Tribe, a clan of Shinto animal spirits living in the forest. The Spirit Tribe is at war with the invading gods of Buddhism, echoing the earlier culture clash in “Yamato.” On top of all this, Harima has recurring dreams of being Suguru, a cynical freedom fighter in a dystopian future ruled by the “Church of Light” cult. Both the Spirit Tribe and the 21st century rebels launch plans to find the Phoenix, who exists in both timelines, and gradually the two stories of rebellion start to parallel one another.

The longest story in Phoenix, “Sun” covers two thick volumes of the Viz edition. As in several previous stories, the central theme is the corruption of religion by power-hungry leaders. The seventh century plot, with its world of threatened Shinto spirits reminiscent of Princess Mononoke, is the more fleshed-out and interesting of the parallel storylines.

…and there it ends. Both “Strange Beings” and “Sun” play with time travel and the idea of characters from different eras meeting, which gives the impression that Tezuka was building to an ultimate clash of timelines. Or maybe he had no particular ending in mind, and was just having fun building his own universe. Either way, this was an artist who thought big. And if all we get out of Phoenix, in the end, is twelve of Tezuka's best and weirdest stories, that's something amazing.

discuss this in the forum (20 posts) |