House of 1000 Manga

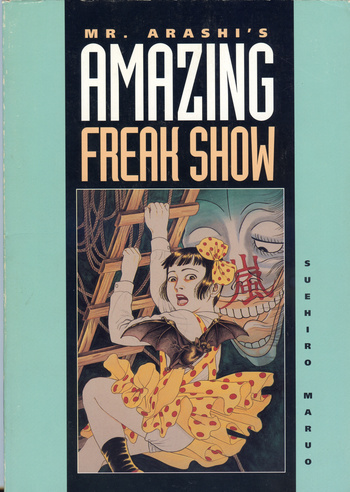

Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show and The Strange Tale of Panorama Island

by Shaenon K. Garrity,

Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show and The Strange Tale of Panorama Island

Back in the ’80s and early ’90s, when manga and anime first started to find a sizeable cult following in the U.S., horror was one of the most popular genres. To American manga fans—mostly college students who traded material around conventions and campus clubs—the willingness of Japanese artists to depict graphic violence in cartoon form was fascinatingly transgressive. Nowadays, horror is a much smaller market. Maybe American tastes have changed, maybe publishers have gotten more conservative, or maybe it's that graphic horror manga (especially by stylish-but-gruesome artists like Junji Ito and Shintaro Kago) has a loyal following in the scanlation community, so nobody has to pay to get grossed out anymore.

Suehiro Maruo is one of the most extreme horror artists, the kind whose drawings make people sick to the stomach, and in the 1980s only alternative publisher Blast Books, purveyors of every book about drugs, freaks, and 1950s cornpone you ever found next to the toilet in off-campus shared housing, had the guts to publish his work. (For the record, I own a lot of Blast Books titles, including everything they've ever published about vintage instructional films. But I digress.) Blast's groundbreaking anthology of out-there manga, Comics Underground Japan, included Maruo's “Planet of the Jap,” a pornographic fantasy/nightmare depicting an alternate history where Japan conquers and brutally subjugates the United States. Blast also published Mr. Arashi's Amazing Freak Show, a survey of Maruo's obsessions with violence, torture, and grotesquerie.

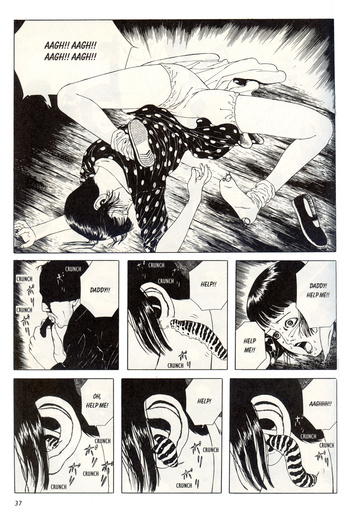

Maruo is one of the premier ero-guro (erotic grotesque) manga artists, but with more emphasis on the guro than the ero. In Mr. Arashi, an orphan girl named Midori finds herself sold as a servant to a low-budget freak show, where she's emotionally, physically and sexually brutalized by the performers. In a typical chapter, Midori adopts a puppy, which the freaks cook and serve for dinner just to upset her. Another chapter ends with Midori naked and tied up, thinking, “All I want is to go on a field trip…” All of this plays half as genuine horror, half as parody of vintage pulp fiction; the Japanese title is Shojo Tsubaki (Camilla Girl), the name of a stock damsel-in-distress character in 1920s kamishibai.

Things get slightly better for Midori with the arrival of Masamitsu the Bottled Wonder, a dwarf magician who seems to have genuine supernatural powers. Masamitsu takes a shine to Midori and protects her, and she falls in love with him. (Their romance is treated with melodramatic sincerity, despite Midori being apparently about twelve years old.) But Masamitsu is a dangerous character, and soon Midori learns that no one in her weird world can be trusted. After throwing every bizarre image he can think of onto the page—snake women and human worms, lepers eaten by ants, grotesque sex scenes, bodies growing and shrinking and twisting into impossible shapes—Maruo ends by smashing any semblance of reality and leaving Midori alone on a blank page, crying.

Maruo's fascination with antique horror comes through not only in the period setting, but in his deliberately old-fashioned artwork, which borrows both the vapid prettiness and the off-kilter creepiness of earlier eras. His style is sometimes described as modern muzan-e (“atrocity pictures”), a 19th-century branch of ukyo-e devoted to theatrical scenes of gory violence. But above all periods, Maruo seems to love the 1920s, the decade when Old Japan and New Japan clashed, tradition soured into decadence and modernity into militarism, and the experimental artists of East and West discovered one another.

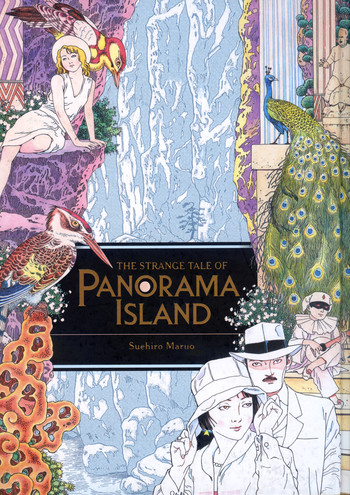

This fascination comes out in full force in Maruo's most recent manga, The Strange Tale of Panorama Island, which is much less graphically gruesome than his early work—so much less so that it can be published in a classy hardcover from Last Gasp and look perfectly respectable on your bookshelf. Until some unsuspecting visitor sits down and reads it, anyway. Panorama Island is an adaptation of a 1926 novella by Edogawa Rampo, a figure who looms large in 20th-century Japanese literature. The father of Japanese detective fiction and inventor of the “phantom thief” character appropriated by countless manga, Rampo also specialized in eroticism, surrealism, and horror. (His pen name is the Japanese transliteration of “Edgar Allen Poe.”) One could hardly pick a better match for Maruo's sensibilities than one of Rampo's 1920s ero-guro stories.

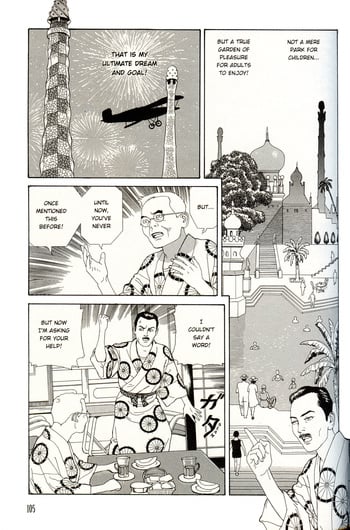

When the scion of a wealthy family dies in an accident, a frustrated young writer sees an opportunity: he and the dead man look remarkably alike, so he will pose as the deceased, pretend to have miraculously survived, and claim his fortune. Rampo and Maruo describe the writer's scheme as plausibly as they can, but it's transparently a plot device to get them to the second half of the story, the part that really interests them. That's when the writer, Hitomi, spends his vast fortune on the art project of his dreams: the most spectacular pleasure island in history.

All semblance of logical narrative falls away when Hitomi finally tours the island, and Rampo and Maruo lavish detail on its glorious, horrific, impossible features. A mile-long underwater glass tunnel! Optical illusions that create massive staircases and endless gardens! Enormous statuary! Swan boats (a nod to real-life hedonist Ludwig II and his pleasure palace, Neuschawnstein Castle)! “Dream machines that produce nothing”! And the island's inhabitants: jesters, human statues, women swimming in pearls, and beautiful naked people both male and female (mostly female in Maruo's rendition, though Rampo probably would have preferred more dudes). As the tour continues and the festivities build to an orgy of sex and violence, the already impossible island becomes increasingly surreal, incorporating imagery from artists of the bizarre ranging from Aubrey Beardsley to Henry Darger to Hieronymus Bosch.

And Maruo is up to the task. In early works like Mr. Arashi, his art is arresting but stiff and sometimes (okay, often) confusing. Twenty years later, he's not only an effective cartoonist but a stunningly skilled illustrator, a master of the vintage illustration styles he clearly loves. This is one of the most beautiful manga you will ever read. But the loveliness of the art only makes the horrific elements of the story that much more disturbing.

Panorama Island certainly isn't as graphically sickening as Maruo's old ero-guro work. Instead, it gets under the skin. And Mr. Arashi and Panorama Island end on a similar note of nihilism, of the author coming out the other end of his wildest fantasies and finding nothing left to dream or fear. Like the manga industry, Maruo has changed since the 1980s: more polished, more respectable, less inclined to indulge in the crude and sloppy and in-your-face weird. But underneath his new veneer of class, he's gotten far better at pulling the rug out from under reality.

discuss this in the forum (8 posts) |