House of 1000 Manga

Lady Snowblood

by Jason Thompson,

Snow, darkness, women, swords: Lady Snowblood's biggest mark on America was the fight scene at the end of Kill Bill Vol. 1. The heroines face off in a snowy backyard, spraying sparks and spilling blood, and it's a ghostly parallel of a scene in Lady Snowblood. Even the fact that it's obviously filmed on a sound set, like the film, only makes it more manga-like; as unreal as Kazuo Kamimura's artwork, as ritualistic and dead-serious as a play. Of course, Quentin Tarantino was influenced by the 1973 film adaptation, not the original manga, just like how Shogun Assassin inspired a wave of American samurai-themed films in the 1980s. And both Shogun Assassin (aka Lone Wolf and Cub)and Snowblood are based on manga written by Kazuo Koike, the most prolific, wild, influential men's mangaka of a wild and violent decade.

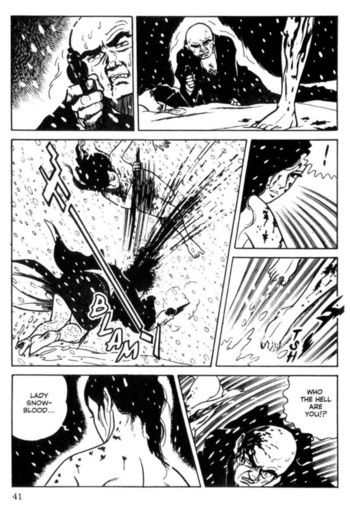

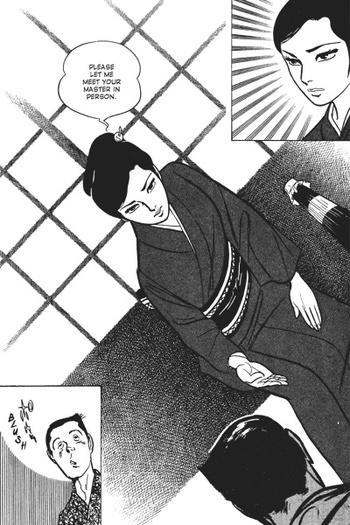

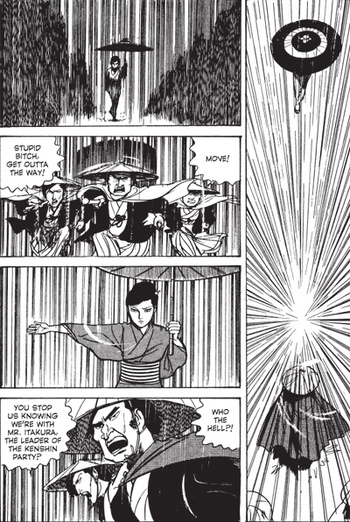

Like Lone Wolf and Cub, it's the tale of a master assassin in old Japan. Yuki is Lady Snowblood, an swordswoman and killer (in Japanese she's Syurayukihime, "Hell Snow Princess", a pun on Shirayukihime, "White Snow Princess" aka Snow White). Beautiful, young and mysterious, she accepts missions of murder and sabotage, charging top yen for her services. Unlike the scruffy drifter Oogami Itto in Lone Wolf, who is like a human tank and pretty much obviously trouble from the moment you look at him, Yuki uses subterfuge and disguise. When she meets clients, she keeps her eyes downcast, her speech incredibly formal, traditionally 'womanly'. ("It is not right for me to ask your master's audience without first introducing myself.") But in battle, she's deadly, somersaulting through the air, slashing men's throats out, getting her target even if she's nude. (She occasionally ends up nude, but she isn't always nude, unlike, say, Kekko Kamen.)

But like Oogami Itto (and unlike, say, Golgo 13) Yuki has a goal beyond killing for profit; she pursues a secret mission of REVENGE. As we soon see in flashback, Yuki was born in prison. Her mother was Sayo, a prisoner serving a life sentence. Her father was unknown; Sayo had slept with any man she could find, monks or prison guards, because she needed a child to carry out her dream of REVENGE. Years earlier, Sayo's husband and son had been murdered, and Sayo had been raped, by a vicious gang of four criminals. Sayo herself managed to kill one of the men, but in return, she was captured and sentenced to life in prison. "I'm a life prisoner. I won't be able to get outta here alive. But my baby—she can leave right away. I'll have my baby deliver my vengeance after I die!" Sayo dies in childbirth, leaving Yuki in the care of one of the other prisoners, an old woman. Before she expires, Sayo makes the woman promise to tell her daughter about her mother's sacrifice, and train the daughter into an instrument of her mother's grudge.

And so the bloodshed begins. But despite the famous fight scene from the movie, Lady Snowblood actually has relatively little fighting; although her sword mastery is never in doubt, Yuki's technique is more brains than brawn. Yuki uses allies: a friendly priest, a gang of pickpockets, a gang of beggars. They don't help her in fights, but they provide logistical support and help her track down her prey. She has numerous skills, from art to disguise to thievery, and she doesn't always end things with murder if there is another, better way to ruin her target's life. In one story, she poses as an artist and sells her skills to a brothel owner to draw beautiful paintings on his fleet of rickshaws…but, in one of the manga's best twists, the paintings themselves prove to be as deadly as a sword. She poses as a Buddhist monk, as a nurse in a hospital, and in one story, as a fancy Westernized lady with a hat and a petticoat.

Open up a random page of Lady Snowblood and an American reader is likely to think it takes place in the samurai era, but actually, the story takes place in the Meiji era, sometime in the 1890s. In one chapter, Yuki spies on her target using a telescope from the top of the Ryôunkaku, Tokyo's first skyscraper. Like in Lone Wolf and Cub, Kazuo Koike mixes historical fact and fiction, giving the manga an educational gloss. Unlike Lone Wolf and Cub, in Lady Snowblood there is a strong sexual focus to these factoids. The story takes place almost mostly in the Yoshiwara brothel district. A story about photography, a relatively new invention at the time, hinges on the production of porn. A story about rickshaws focuses on rickshaw sex, the Meiji-era equivalent of sex in a taxi. (Koike Historical Note: "The reason behind the extreme popularity of the jinriksha was the car sex.") As if Koike could predict the future, there's even a story about "bamboo ladies," basically a Meiji-era equivalent of body pillows, although without Kudryavka Noumi screen-printed on them. The sex focus is certainly based on Koike's own interests, and perhaps also on the fact that the manga ran in the men's magazine Weekly Playboy. Of course, sex is timeless, but it's hard not to get the impression that Koike is expressing 1970s-era sexual fixations in historical trappings: porn, women in prison (amazingly, that's one of the least exploitative story arcs), rape-and-revenge. Koike's manga are like '70s exploitation flicks, except his manga were so influential, it's hard to tell who was copying who.

Of course, in any historical story the author picks and chooses what they focus on, and another area Koike focuses on is the encroaching influence of the West. The Meiji era was a time when Westernization and 'modernity' merged and clashed with traditional Japan; reformer Arinori Moriat one point advocated making English Japan's official language, and in 1884 Yoshio Takahashi, a Japanese eugenicist inspired by Western racist eugenics movements, wrote an essay proposing mass-scale crossbreeding between Japanese and white Europeans "to improve the Japanese race." Koike calls out these extremes as examples of "Westernization gone mad," and Yuki's assassination skills are the solution. One storyline involves the Rokumeikan, a European-style dance hall which was controversial for hosting such decadent Western practices as male-female ballroom dancing. (Of course, actual prostitution was totally kosher and legal in Japan at the time.) Wikipedia writes "its image as a center of dissipation was largely fictional", but to Koike, it's an "indecent house of promiscuity" where couples dance till they drop and then bone on the floor, and Yuki is hired to destroy it and kill some big-nosed white guys in the process. Westernization isn't the Big Bad in all the stories—in one, a sympathetic businessman tries to fund a Western-style panoramic painting in Tokyo—but Koike isn't above playing to Japanese nationalistic sentiments and insecurities. Yuki tempts one of her victims by wearing exotic Western underwear: "It's called 'bloomers.' It's the undergarment worn by the Westerners." Another chapter ends on a cliffhanger of Yuki captured and menaced by a man whose penis is so enormous he's never been able to have sex. Her captor reveals his dream is to have enough money to go to the West and find a woman big enough for him: "If I travel abroad, I can find women bigger than me! I'm gonna save money and go to the land of the Caucasians!"

Call him sexist, misogynist or both, Koike is Persona Non Grata for how women are treated in his manga. Given his track record, it's almost surprising that in Lady Snowblood Yuki is never sexually assaulted and her body is relatively rarely exposed. (Perhaps a recognition that Kamimura isn't the sexiest or best draftsman; indeed, the manga reads better for its composition and patterns rather than individual objects; it's not about bodies or shapes as much as about areas of black and white, darkness and blood and snow.) Yuki is threatened with rape, but she always gets out of it at the last minute (or second) without sweating too much, and ultimately retains agency over her own body. In one of the very first scenes, in an interview at a brothel, a client protests that her price of 1,000 yen is too high for an assassin of unproven skills. Yuki instantly whips her sharp steel hairpins out of her hair and, without looking behind her, flings them dead-center into two dildos on a shelf. (Koike Historical Fact: "Every brothel, without fail, has a family altar that enshrines a bell and two penis-shaped ornaments.") The client pays up. You don't need to be Sigmund Freud to get the message.In another story she uses the cover identity of a traveling dildo saleswoman.

Of course, Yuki is a cold, steely object in other ways as well; she's the 1970s version of what would become the female robot archetype, the Dark Angel type, the coolly sexless/inhuman superheroine/assassin. The Count of Monte Cristo, the guy in Old Boy, even Ogami Itto, were originally semi-ordinary people driven to inhuman extremes in pursuit of revenge, but Yuki is a sword forged for one purpose, sworn to revenge since the day she was born. "In a way, I'm a phantom of my mother, not her daughter…I am a vehicle of retribution who roams in search of my mother's sworn enemies…I was born into this world as a vessel of the Kashima family's revenge!" Of course, there is no doubt or hesitation involved, no question that Yuki would resist devoting her life to a mother she never knew. Perhaps absolute self-sacrifice was considered even more appealing in a female character than a male one. Like a lipstick-rather-than-butch version of Oscar in The Rose of Versailles, Yuki is basically a sworn virgin who lives asexually, taking the "manly" role of killing and kicking ass and taking names. Her pseudo-asexuality is typical for a woman in a leading role in a men's manga; the straight male reader both lusts after Yuki and projects himself onto her. Given her sympathetic starring role, Yuki is spared most of the abuse that Koike's other female characters suffer because, if she suffered that abuse (or heaven forbid, actually felt mutual attraction for a man), male readers might feel it too. Or worse, get jealous. Most of the sex in Lady Snowblood is lesbian sex, usually but not always depicted as predatory in the stereotypical fashion (although for that matter, all the straight sex in Koike's manga is predatory too). Instead of being raped, it's Yuki who, in two or three storylines, rapes other women, or commands a man at swordpoint to rape them.

It's a fairly short manga, at only four volumes, all translated by Dark Horse. There are few continuing characters other than Yuki, and no other continuing young female characters; although Quentin Tarantino upped the stakes all Queen's Blade style by having badass Uma Thurman fight equally-badass Lucy Liu and Daryl Hannah, Lady Snowblood never really fights any female opponents (at least none worthy of mention). Perhaps that's why it didn't run longer,or perhaps Kazuo Koike just got tired; like many of his manga, the ending of Lady Snowblood is fairly abrupt, although it does have an ending and doesn't just stop like, say, Path of the Assassin. It's a fascinating, sleazy, violent tour of the Meiji Era, as Yuki hacks and slashes her way through Japan in pursuit of her goal.

One of Koike's greatest strengths as a storyteller is his willingness to go off on tangents. Towards the end of Lady Snowblood, a strange plot thread intrudes; Yuki seeks out 'the wanderer,' a bearded old novelist, and tells him the story of her life. The old man writes a bestselling novel about her—a newspaper serial, a very Meiji Era medium—and Yuki's enemies read the novel, which freaks them out so much they come out of hiding, just as Yuki planned. It's a fabulously odd ending, and appropriate too: Yuki, formerly the female protagonist, becomes the model for a story written by a man, cleaning up the old man's studio and stripping naked to model for the artists drawing the illustrations. How could it get more meta? The ending of Lady Snowblood leaves some room for a sequel, so in 2006 Koike returned to Lady Snowblood with Ryōichi Ikegami as artist, creating the (untranslated) Lady Snowblood Gaiden. I haven't read it yet, so I don't know how it is, but the fact that it only lasted one volume isn't a huge endorsement. But the ending of the Lady Snowblood movie, the very last scene, is just fine.