House of 1000 Manga

Ohikkoshi and Emerald

by Shaenon Garrity,

Ohikkoshi and Emerald

I love short manga, but it seems to be a hard sell to comics fans, both in Japan and abroad. It's easy to see why publishers prefer long series that can keep generating sales indefinitely; for the last several decades, the trend has been toward longer and longer manga, and hit series are encouraged to keep running indefinitely. Yet your average manga-ka usually has a fair number of short works under his or her belt: short stories done as test pieces to break into the big magazines, side projects for specialty magazines or doujinshi, short-lived series that got cancelled after the first couple of chapters. What does an artist have to do to get miscellany like that published in the U.S.?

I love short manga, but it seems to be a hard sell to comics fans, both in Japan and abroad. It's easy to see why publishers prefer long series that can keep generating sales indefinitely; for the last several decades, the trend has been toward longer and longer manga, and hit series are encouraged to keep running indefinitely. Yet your average manga-ka usually has a fair number of short works under his or her belt: short stories done as test pieces to break into the big magazines, side projects for specialty magazines or doujinshi, short-lived series that got cancelled after the first couple of chapters. What does an artist have to do to get miscellany like that published in the U.S.?

Well…he could be a big name who's had work in English translation since the dawn of time, or at least the early ’90s, and has a rock-solid relationship with a major American publisher. An artist who's not very prolific—maybe he only has one long ongoing series—so publishers leap at the opportunity to license anything he puts out. Famous, established in the U.S., but not prolific: someone like that would be a perfect storm of gotta-get-the-whole-back-catalog. Someone, in fact, like Blade of the Immortal creator Hiroaki Samura.

It's impressive how well-known and influential Samura's work is in the English-reading world given that the 30-volume Blade, which only recently wrapped up in Japan, is his only lengthy or particularly successful work. All of Samura's other published manga are stand-alone stories or short gag series; he's also done a smattering of illustration work, especially erotic and ero-guro material. He was one of the creators synonymous with Dark Horse Manga in the 1990s, when it was the go-to publisher for stylish but gritty seinen artists like Samura, Katsuhiro Ōtomo, Masamune Shirow, and anyone trashy-brilliant enough to team up with Kazuo Koike. Of course Dark Horse also published cute stuff like Oh My Goddess! and What's Michael?, but that's another column. This week is all about blood, guts, and sadistic nude women!

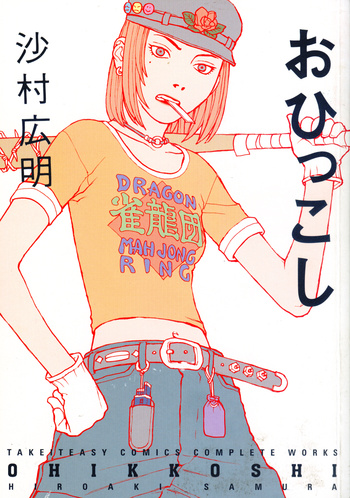

Dark Horse has published two collections of Samura's short manga: Ohikkoshi, which hails from the early 2000s, and the more recent and eclectic Emerald. Most of Ohikkoshi is devoted to the titular story, a five-part series following a group of artsy college students. Everyman protagonist Tono has a crush on the beautiful, flirtatious, financially struggling Akagi, who's determined to remain loyal to her boyfriend while he does volunteer work in Zambia—and what drunken slacker can compete with a guy like that? Meanwhile, Tono is blind to the charms of his tomboyish best friend Koba, whose rock band performs nonsensical lyrics which the manga helpfully reproduces in full.

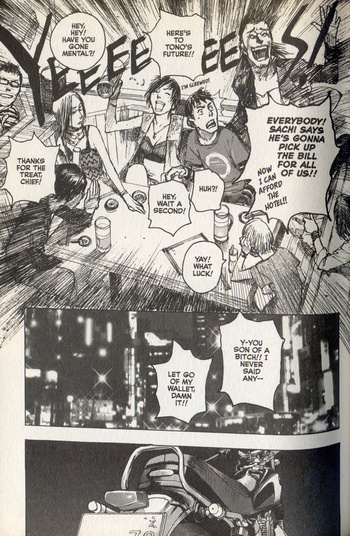

Individual chapters of “Ohikkoshi” run the gamut from typical slice-of-life comedy (Tono visits Akagi at her job at a hostess club and gets roped into a drinking contest) to gonzo humor (a handsome foreign professor turns out to be an Italian hit man who has sworn revenge on the people of Japan for reasons related to the cup noodle industry). Samura peppers everything with fourth-wall-breaking commentary and 1990s Japanese pop-culture references, which the Dark Horse edition does its best to explain. Thank you, Dark Horse endnotes! How I love you! But the charm of the story is in its plausibly human characters and their lovingly drawn world, a post-bubble-economy Tokyo populated by jaded but shyly hopeful young people trying to carve out a place for themselves. Samura's sketchy-realistic art is strange for a humor manga—it's not a style that screams “comedy”—but oddly fitting for an awkward, sensitive, off-the-cuff dramedy.

The other miniseries in Ohikkoshi, “Luncheon of Tears Diary,” takes the manic energy of “Ohikkoshi” to the next level. Initially the tongue-in-cheek story of a struggling shojo manga artist whose editor keeps passive-aggressively pushing her to draw more explicit material (“Is he telling me to turn ‘Dream Lunch’ into an erotic comedy?!”), it quickly veers off into a series of vignettes parodying various manga genres. In her search for artistic experience, the heroine becomes a prostitute, a yakuza mistress, a mahjong master, and on and on until Samura runs out of steam and/or meets his page count. It feels very stream-of-consciousness and doesn't have much point, but heck, send-ups of mahjong manga are always funny. Still, it's a much less finished work than “Ohikkoshi” and, like the brief travel diary that finishes out the book, seems to be included mainly to push up the page count to a respectable level.

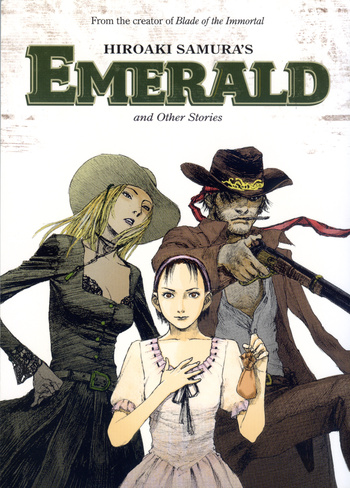

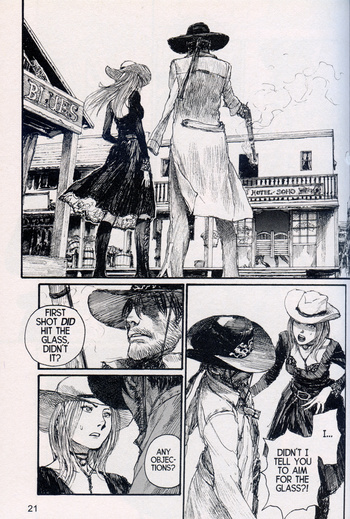

Compared to Ohikkoshi, Emerald is more polished and self-assured; even Samura's artwork has grown more precise, taking on a crisp finish. It seems designed as a portfolio showcasing the widest possible range of the artist's work: see, he can draw more than just samurai! The title story, arguably the strongest piece in the collection, is a Wild West adventure that makes you wish there were more Western manga. “Brigette's Dinner” and “The Kusein Family's Grandest Show” are erotic stories with surreal, sadomasochistic overtones; the former is unfocused and rambling (probably in a deliberate attempt to mimic the stiltedness of old French erotic novels), the latter disturbing and memorable. “Shizuru Cinema” starts as sex comedy and turns into science-fiction horror, a neat trick if you can pull it off. “Youth Chang-Chaka-Chang” is a short comedy story reminiscent of the humor in “Ohikkoshi,” although Samura notes in the afterword that it was supposed to be porn: “I remember realizing, ‘Ack! I forgot to put in the ‘eros’ component!’ So, scrambling, I made sure I showed nipples on the final page.” There's even a brief mahjong manga. Some of the stories are excellent, others just so-so—the eternal pitfall of anthologies—but all are at least interesting.

The most disposable material in Emerald is the running gag series “The Uniforms Stay On,” in which three high-school girls chat about their interests and current events. In the 1990s and 2000s everyone had to do a kogal comic, and frankly it doesn't feel like Samura is especially into the trend, as much as he enjoys drawing pretty girls. He admits in the afterword that he doesn't know anything about the subjects his teenage characters discuss and was reduced to picking newspapers out of the trash to catch up on current events. (Looking over the afterword as I write this, I realize I would probably read a whole non-manga book of Samura's observations on life.) Last week's “House of 1,000 Manga” subject, Usamaru Furuya, knocked the pervy kogal gag comic out of the park with Short Cuts, and anything else feels halfhearted.

If the stories in Emerald have anything in common, and they try not to, it's their creator's unmistakable underlying tone: sexy, dangerous, a little kinky, a little grim, with a sardonic and self-referential sense of humor. In Japan, the collection was entitled Sister Generator because of its focus on female characters, and an interest in women is another of Samura's hallmarks. Even his macho action manga tend to include a lot of female characters, and he loves not just drawing attractive women but really observing them: their individual faces and figures, their clothing, their body language. (That's one thing Samura has over Furuya as a kogal artist: whereas Furuya seldom deviates from the same idealized female face, the schoolgirls in “Uniforms” look completely different from one another.) He loves sex, violence, pretty clothes, grotesquerie, women with moles, and the occasional game of mahjong. And without this buffet of short manga, where would we get the chance to love them too?

discuss this in the forum (4 posts) |